A localized prosthetics industry would help Arab Paralympians and ordinary people alike. But is it growing fast enough?

Microprocessor–controlled C–legs. LUKE arms. Powered mobility exoskeletons. The craft and science behind creating prosthetics, orthotics, and many other mobility tools have undergone leaps and bounds in terms of how they meet the personalized needs of their users. The post‒World War II landscape accelerated innovation due to sheer demand, leading to the development of prosthetic limbs that were more functional and comfortable. The following decades saw breakthroughs in muscle‒controlled prosthetics and even bionic limbs. In the past few years alone, more cost-effective approaches, such as using 3D printing, have allowed for greater accessibility for those in need. These advancements have greatly improved the quality of life for individuals with limb differences, allowing them to engage in activities they may not have thought possible.

In the Middle East, the field of mobility tool engineering has also seen substantial expansion. Either due to increased demand from local communities with disabilities or mobility differences (or perhaps the need to depend less on foreign imports), local companies are investing in the research and development of prosthetic and mobility tools, leading to innovations that cater to the specific needs of the region. Saudi Arabia’s HealTec is the country’s first prosthetics and orthotics manufacturer, a rarity in the region.

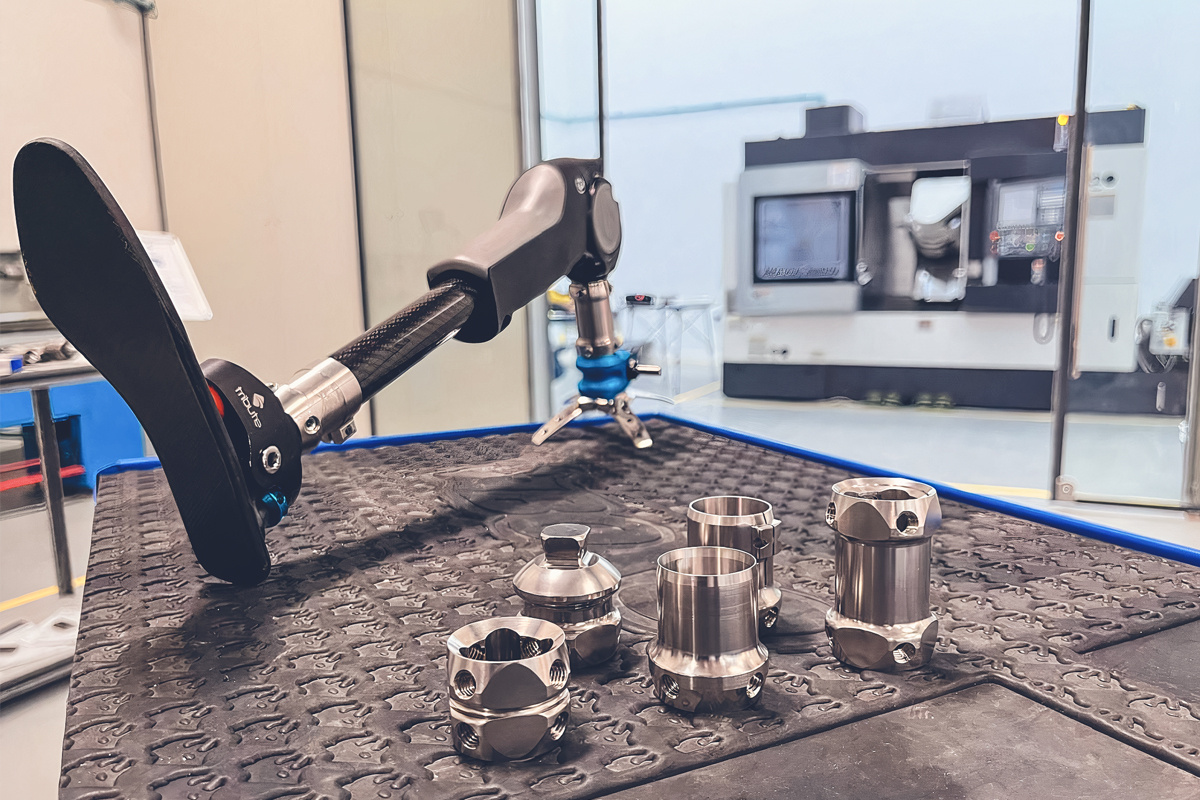

Founded in 2020, the company recognized a gap in the region’s ability to meet the rather urgent needs of patients requiring mobility assistance or rehabilitation. Founders Dr. Hashim AlZain and Eng. Ayman Noori recognized that patients with mobility needs were often met with prohibitive waiting periods and costs for devices manufactured abroad. Their goal was to provide high‒quality, affordable prosthetic and orthotic solutions tailored to the unique requirements of individuals in Saudi Arabia and the Middle East. The means through which this is accomplished appear simple: Leveraging local expertise and resources. It has eight 3D scanners that are solely dedicated to determining the exact measurements of each individual patient. Despite its success, this standalone establishment has been met with its own unique set of challenges and gaps.

“The availability of the raw materials is a major setback for production in Saudi Arabia,” explains Eng. Abdullah Alraddadi, production manager at HealTec. “Specifically, the high‒performance materials that are most suited for athletics and sports.” According to Alraddadi, there is no fundamental difference in the manufacturing of an athletic prosthetic. Since each disability, mobility difference, and rehabilitation need is unique, each prosthesis must be tailored to their specific requirements.

The difficulty isn’t in how it’s done, but rather in what it’s made of. Non‒athletic mobility tools, for example, might focus on mimicking natural limb appearance using materials like thermoplastics, silicone, aluminum, and stainless steel. On the other hand, an athletic prosthesis must be lightweight, strong, and have a high energy return that emphasizes the use of advanced materials such as carbon fiber, titanium, and high‒performance polymers.“Functionality is the most crucial aspect for the athletes, then comes comfort, and lastly aesthetics,” adds Alraddai. “However, once the prototype is approved and the functionality is proven, minor tweaks and adjustments are integrated into the design to achieve the level of comfort that would allow the athlete to reach maximum performance.”

For some athletes, those tweaks are crucial to not just their performance, but also to how long they can comfortably use their prosthesis. For Aya Ayman Abbas, the first female Egyptian and youngest Paralympic swimmer to participate in the Rio 2016 Paralympics, the only time she is mobile without her wheelchair is when she is competing. “I prefer it to be more of a ‘lifestyle’ wheelchair. My actual sports performance has nothing to do with using it,” says Abbas. “But its specifications are honed to my measurements and needs. The cushion, for example, must have a very particular firmness and shape—it’s where I spend all my time! As a mobility tool, it must be fast, it must be light, and it must be bespoke.”

Egypt has also made progress in advancing its domestic manufacturing of prosthetics, orthotics, and mobility tools like wheelchairs. In 2022, the Egyptian government announced the allocation of EGP 5 billion annually to support people with disabilities, and the construction of an industrial complex to localize prosthetics production. Although Egypt has competed in the Paralympics since 1972, the effects of these initiatives have yet to align with the needs of even three-time medalists like Abbas, who still faces one major hurdle. “Accessibility,” she says. “[Mobility tools] are not easy to make in the region, and they’re incredibly expensive. I actually need to change my current wheelchair; I’ve had it for years and need to take new measurements. To do that, I have to go abroad, and it’s a lottery-based system.”

Progress persists despite some setbacks, but more support is needed to ensure that athletes with disabilities have equal opportunities to excel in their sports. According to Abbas, the solution might lie in improving awareness. Additionally, by continuing to invest in research, development, and local manufacturing, the industry can better meet the growing needs of its users, paving the way for a more inclusive and mobile future.