THE pain Victoria Abbott-Fleming feels every day in her legs is excruciating. One minute it’s like they’ve been dipped in acid, the next as if they’re being stabbed with ice-picks.

This kind of pain would be awful for anyone, but for Victoria, 45, this is compounded by the fact her legs were amputated years ago.

It’s something that affects nearly everyone who’s undergone an amputation, including the hundreds every year in Ireland who have the surgery as result of diabetes complications.

Victoria, who is married to Michael, 58, was a young lawyer with everything to look forward to when, aged 23, she fell down some steps at work.

Initially the fall caused just a minor cut and some bruising on her right shin, which swelled up. But the swelling got worse – ‘the shin was just so sensitive, even getting dressed was agony. I couldn’t go back to work.

‘As the months progressed, I had to use a wheelchair.’

Over seven months, Victoria saw 39 different specialists, including pain consultants and neurologists, before being diagnosed with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), a condition that affects around 700,000 people in Ireland every year. It’s thought to be caused by the body reacting abnormally to an injury.

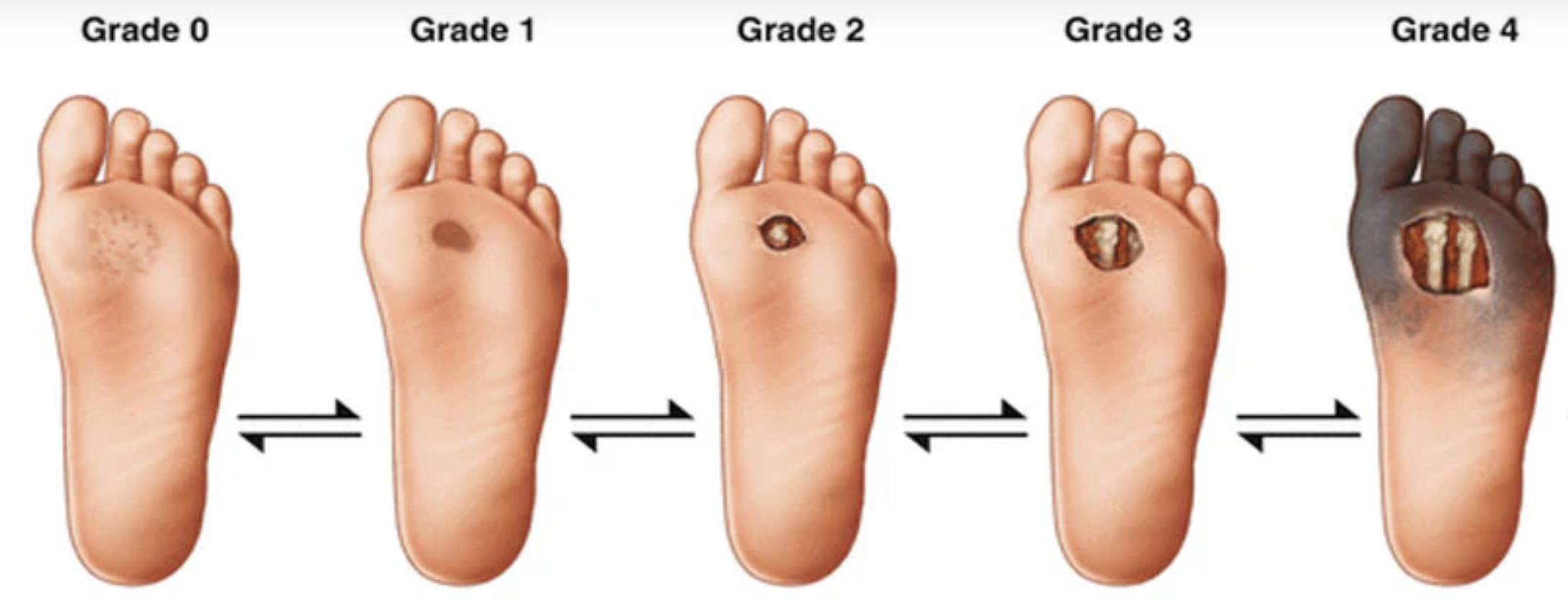

As Victoria’s leg became more swollen, the skin started to split, leading to an ulcer that wouldn’t heal.

‘It was constantly weeping and the smell was just awful.’

Over the next two years, she was in and out of hospital with infections until, in 2006, with no skin on her leg from the knee to the toes, she needed amputation of her right leg below the knee.

SHE and Michael married three months before the operation – and Victoria hoped that the surgery would mark the beginning of a new chapter.

But a few months later, half asleep in bed, she felt a ‘twinge – in the leg I no longer had’.

Over time, this developed into pain ‘that got worse and worse’. It was, she says, ‘so cruel because it was just like CRPS except in the parts of the body I didn’t have’.

She’d developed phantom pain syndrome (which also affected her other leg following the second amputation in 2014).

‘Phantom sensations occur in almost everyone who has an amputation,’ says pain specialist Dr Deepak Ravindran.

Around 700 limbamputations are carried out in Ireland every year, often as a complication of diabetes – phantom pain tends to occur within the first six months after the operation.

‘Whilst you may have lost a limb, the brain’s “map” of the body is still intact,’ explains Dr Ravindran. ‘That area still has a neural circuit in the brain which continues to fire out messages that there’s a problem in the leg even though there isn’t.’

This leads to sensations of pain, itching, tremors, burning or pinching, in the missing limb. These symptoms can range from mild to severe and last for seconds, days or even years.

Pain medication can help but is not always effective.

Other treatments aim to block rogue pain signals sent by the brain, such as spinal cord stimulation (via an implant placed in the spine surgically) and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS machines).

Some patients are offered mirror therapy which involves doing exercises beside a mirror which covers the affected limb.

Seeing the reflection of the unaffected limb working normally tricks the brain into thinking the amputated limb is still there, says Dr Ravindran.

This reassures the brain all is well, calming the ‘hyper-alert neurocircuits’, so it won’t send out false pain signals.

The sooner this therapy is used the better – after a year or two it can be hard to reprogramme the brain: success is also individual, says Dr Ravindran.

One 2019 study found that mirror therapy reduced pain by 40 per cent in 89 per cent of amputees. Unfortunately for Victoria, who has founded the CRPS charity Burning Nights, it didn’t work.

After nearly 20 years of pain, she relies on her pain ‘toolkit’, which includes distraction therapy – ensuring her mind is busy – as well as pacing her activities and chores (doing half the washing, for instance).

‘It’s taken a long time to get to this point’ says Victoria, ‘but I’m now able to manage my pain and, in many ways, live well. I feel lucky despite the many setbacks.’

For more details of the charity, see burningnightscrps.org

AIR New Zealand has once again captured the title of safest airline in the world. The national carrier retook the top spot for 2024, dethroning its neighbour Qantas, according to AirlineRatings.com, which compiles the rankings each year. There are no Irish airlines in the top twenty safest airlines, and only one British carrier— British Airways. So should you immediately cancel any bookings you have on an Irish or British carrier, and instead opt to fly Alaska Airlines (ninth safest airline) or perhaps Hawaiian Airlines (no. 20)? No, not at all. Ryanair and Aer Lingus both have exemplary safety records with a clean sheet in Ryanair’s case, and for Aer Lingus no fatal accidents since 1968. But Airline Ratings also take into consideration aviation industry audits, government audits, the age of a carrier’s fleet, and the training their crew receive. So you can pretty much relax. Everyday more than 100,000 flights depart and land without incident. Statisticians have deduced that travelling by car is about 100 to 120 times more dangerous than flying; travelling by motor cycle is 300 times more dangerous. So just strap yourself in and forget about turbulence. Scary though it seems, your main risk is bumping your head on the overhead bins if you haven’t strapped yourself in. What you do need to remember — but if you forget it doesn’t matter — the first four minutes of the flight test the aircraft. The last four minutes test the cockpit crew.

Although several presidents have boasted Irish roots, Donald Trump is the only one to have owned a golf course His Doonbeg club, designed by Greg Norman, is seen as a very good, big dune links course, but probably not in the top league with, say, Royal County Down, Royal Portrush or Portmarnock. A friend who works down in Clare tells me that President-elect Trump’s nickname in that neck of the woods is ‘Pele’. Apparently if he’s near his ball and it’s not in an advantagous lie, he whistles nonchalantly and nudges the ball with his foot. I probably wouldn’t play golf with him.