Gus Alexiou Contributor Gus Alexiou is a London-based reporter covering disability inclusion.

When it comes to the Paralympics, the Paris 2024 edition of which drew to a close this past Sunday – the word legacy never seems too far from the conversation.

At its heart the Paralympics is a festival of sport and a showcase for how disabled bodies can still, when given access and opportunity, remain strong, powerful, healthy and vital. This natural relationship between the Paralympics and disability sport and fitness across wider society was reaffirmed by U.K. Prime Minister Keir Starmer when he told Channel 4 News during an interview at the Team GB training camp ahead of the Games that the country needed to “match the ambition” of disabled children who would be inspired by the Games by removing access barriers to sports facilities and training.

This gap between ambition and reality across the disability community at large is further fleshed out by data captured by U.K. charity Sense which supports individuals with complex disabilities involving two or more impairments. In Sense’s poll of more than 1,000 disabled people, it was revealed that four in five people living with complex disabilities complete less than 150 minutes of physical activity a week, with more than a third (36 percent) getting less than 30 minutes. NHS guidelines recommend that adults aged 19 to 64 get at least 150 minutes of physical activity a week to help maintain physical and mental health, with those doing less than 30 minutes classed as ‘inactive’.

Almost half (46 percent) of those quizzed said they wanted to be more active to improve their physical and mental well-being but were prevented from doing so due to societal barriers including inaccessible venues and transportation, as well as a lack of skilled staff to support disabled people in fitness settings such as gyms and leisure centers and a dearth of information regarding inclusive sport opportunities.

In a media release accompanying Sense’s data former Olympic Pentathlon athlete Greg Whyte OBE who is now a Professor of Applied Sport and Exercise Science at Liverpool John Moore’s University stated that the health and wellbeing of people with disabilities is being “shockingly neglected.”

During an interview, Whyte further adds, “The Paralympics can be highly inspirational for many but if we want inspiration to become activation then it’s about opportunity. When you look at the results of that polling, what you see is that the opportunity for disabled people to be physically active is far lower than it is for non-disabled individuals simply because nobody's really thought about it from a disabled person's perspective.”

Whyte continues, “For too long, there’s been this social dogma that if you’re in a wheelchair or living with complex disabilities then physical activity does not apply to you. This social barrier exists because of a fundamental lack of understanding that physical activity is critical to health be that physical, mental or social whether you have a limitation or not.”

Through its new Sense Active program funded by a £2.2 million grant from Sport England, the charity plans to support 5,000 more people with complex disabilities to be active by the end of 2027. Sense has redesigned traditional sports, including badminton, tennis and soccer, so people with complex disabilities can start to meaningfully participate and is training 1,000 coaches to help make physical activity more accessible.

Healthy choices

Though it is correct to state that physical activity is important whether you live with a disability or not, the underlying dynamics and stakes governing this is very different for each group. Aside from the obvious access barriers, for many disabled people, physical exercise needs to be a very controlled and deliberate action requiring careful planning. They may not possess either the independence or physical capacity to simply spontaneously decide to “get some steps” in by going for a walk or even expending energy through common activities of daily life such as housework. As disabled people are more likely to live with pre-existing health conditions the costs of inactivity for this group are even higher.

It is a concept well recognized by Mark Raymond Jr who became a wheelchair user at the age of 27 after a diving accident in 2016. Raymond went on to found the non-profit Split Second Foundation, which along with providing a `number of other services for disabled people, operates a fully inclusive gym in New Orleans that helps individuals with spinal cord injury and neurological conditions to work out and maintain their health.

“The big thing we’re doing with the gym is that we're keeping people who normally live a very sedentary lifestyle active,” explains Raymond.

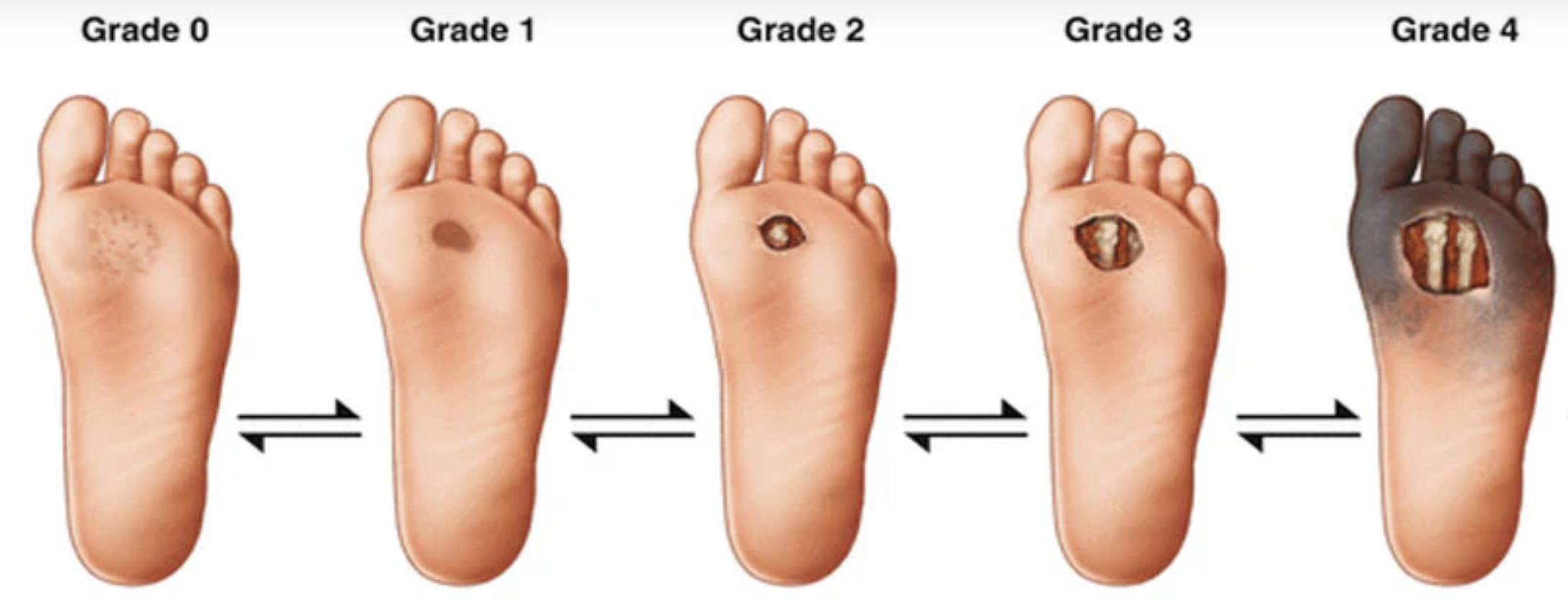

“We’re helping to prevent those secondary complications like bed sores, pulmonary embolisms and cardiovascular issues. This is preventative healthcare and should ideally be funded by health insurance. Many of our health partners fully appreciate the extent to which we are a real community benefit.”

Back in the U.K., Amelia Peckham also lives with a spinal cord injury sustained in 2005 in a quad biking accident at the age of 19. Her reliance on walking aids led to her co-founding the online store Cool Crutches and Sticks a year later and she also has experience of working in boutique gyms in London.

“Many non-disabled people exercise to lose weight or run a marathon but when you have a disability, often you’re exercising to sustain what you've got,” Peckham explains.

“It’s a case of trying to prevent deterioration versus suddenly becoming some sort of fitness model. For me, it's definitely about reducing pain and improving stamina.”

Though initiatives like `Raymond’s Split Second Fitness Centre in Louisiana serve as an almost miraculous and life-affirming exemplar of what is possible, one insurmountable access barrier prevails – geography. Currently, such enclaves of accessibility are thin on the ground and the vast majority of people with disabilities don’t live near such highly specialized facilities.

One trade-off can be that, though some people will only ever be able to use specialized gyms, others may be able to use them temporarily as a safe space to try things out and build up their confidence with physical activity and exercise. Others, even those with relatively severe physical impairments may be able to use a local mainstream gym if just a few accessibility modifications were in place.

Peckham describes what these might entail:

“It's about physically being able to get into the building without a humiliating experience. It's about having front-of-house staff that are usually the least well paid that are experienced enough to have a conversation with someone about what they need and what's best for them as well as having some fitness professionals with experience of working with people with disabilities. I think it’s the front of house staff that are key because if you go and it’s friendly and welcoming then it’s a different ball game.”

Peckham continues, “In the same way as many gyms run over 60s classes there should be one class a week which is adaptive. Currently, it feels like what we have is pockets of good practice in some places and in others no practice at all.”

Whether there will truly be a “Paralympics effect” on adaptive sports and fitness remains to be seen but, to use the words of the Prime Minister, without opportunities that are engaging, impactful and, just as importantly, visible — even the strongest “ambition” towards enhanced health and fitness will eventually fade away.