- Born on August 23, 1834 Bodedern, Wales

- 1851-1854 Apprentice to his Uncle, Dr Owen Roberts working at St Asaph

- 1854-57 Medicine at University of Edinburgh (2 years); University College London (1 year) and then Paris (1 year)

- 1857 – Member of the Royal College of Surgeons MRCS

- 1858 – Worked ‘briefly‘ with his father Evan Thomas as bone-setter ’72 Great Crosshall Street, Liverpool’

- 1860-1869 – General practitioner at ’32 Hardy Street, Liverpool’ a deprived area of Victorian Liverpool

- 1870-1891 – GP and Bone-setter ’11 Nelson Street, Liverpool’ setting up hospital and workshops next door. In 1873 – Thomas’s nephew, Robert Jones arrived at Nelson Street to become apprentice and later his assistant

- Died 6 January 1891, Liverpool

There is a remarkable link between the origins of modern orthopaedics in the UK (and subsequently in North America) and what happened in Anglesey in the 18th century.

The north Anglesey coastline is treacherous. A shipwreck occurred one stormy night between 1730 and 1745. There were only 2 survivors – 2 young boys. They were swarthy and spoke a foreign language. Their origin is uncertain. Possibly they were Spanish because of catholic links with Scotland or possibly Sots speaking gaelic escaping to France following the Jacobite rebellion of 1745.

Evan Thomas

Evan Thomas had 4 sons, the most famous of which was Richard Evans (1772-1851). Note the tradition of naming sons after their father Richard ap (son of) Evan. He earned his living as a farmer. He was a very religious and pious man and woe anyone who mocked him. There is a story about him in a local fair where some young lads started to mock him and one pretended that his shoulder was dislocated. Richard Evans apparently grabbed him and really dislocated the shoulder. The lad had to beg him to reduce the dislocation.

Richard Evans was the father of 3 sons and 4 daughters and they all practised as bonesetters to some extent. Two of the daughters emigrated to America and practised their skills in Wisconsin. Evan Thomas was the most famous. He too decided to emigrate and join his sisters in America in 1831. However, on reaching Liverpool he did not have enough money for the passage. To earn money, he worked in a foundry where he encountered an alarming number of industrial injuries which he naturally treated. Soon word got around about his bone setting skills and Evan Thomas realised he did not have to go to the America to earn a living. He set up his home and surgery in Crosshall Street, Liverpool. Eventually, the Duke of Westminster was one of his patients.

Initially, his relationship with the medical profession was cordial. Many doctors were happy to send him trauma cases. At one time there was talk of appointing him to the staff of the David Lewis (the Northern) hospital but this did not materialise. Gradually, the relationship soured as the medical profession became jealous of his significant earnings from his work.

The Medical register came into existence in 1858 and Evan Thomas tried to get his name on it but failed because of opposition by the Liverpool medical world which was, by now, openly hostile towards him. Disgruntled patients were urged to litigate. Nine attempts were made to sue him including a manslaughter charge but he was never found guilty.

This is Tyn Llan in Bodedern, Anglesey, the home of Evan Thomas’s wife. They had 5 sons and 2 daughter. Interestingly, all 5 sons became doctors. Obviously Evan Thomas realised the days of the unqualified bonesetters were coming to an end. In August 1834 Evan Thomas and his pregnant wife visited the old home. A son was born in Tynllan on the 23rd of August 1834. The house is now a farm outbuilding and has a plaque commemorating the birth of Hugh Owen Thomas, probably the father of modern orthopaedics. Although referred to as meddyg esgyrn (bonesetter), he was medically qualified with LRCP MRCS, which he rarely used.

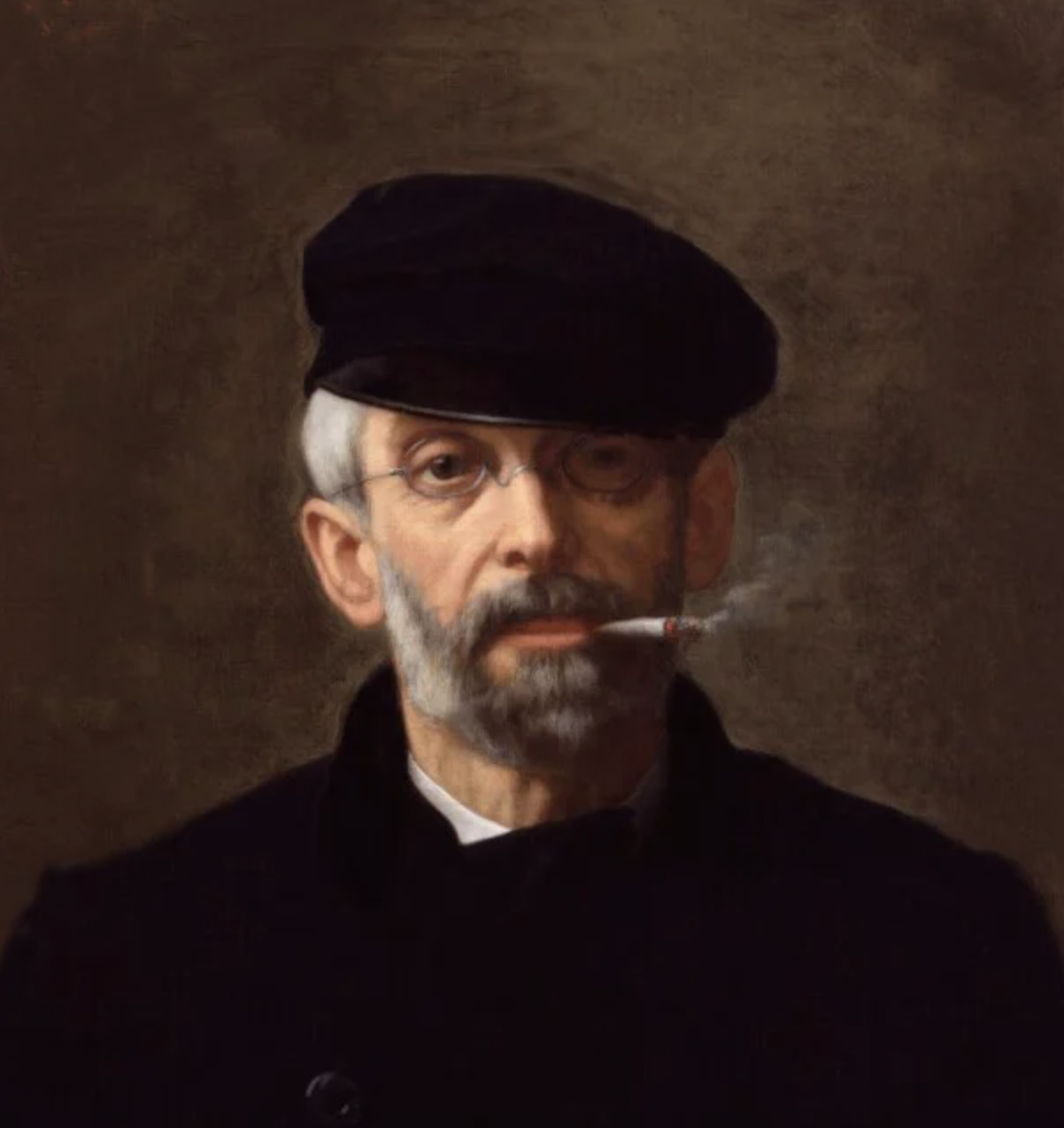

Hugh Owen Thomas was a frail, sickly child. His parents were worried about his health. The Anglesey air was considered to be better for him than Liverpool air so he was sent him to live with his grandparents in Rhoscolyn, Anglesey until he was 13. An eye injury at school caused an ectropion which he protected by wearing a peaked cap pulled low over the eye, one of his trade marks. The others were his frock coat and cigarette. After leaving school, he was apprenticed to his uncle, Dr Owen Roberts of St. Asaph and went to Edinburgh University when he was 21.

.jpg?width=977&height=1045&name=Portrait_of_Hugh_Owen_Thomas_(4671476).jpg)

At this time, Lister was Syme’s houseman and starting his work on antisepsis. However, Hugh was horrified at the number of amputations being performed for tuberculosis as he had seen his father treat such patients conservatively with good results. After 3 years he left Edinburgh to went to University College Hospital in London. All 5 brothers were in London together now. In 1857 he was just about to take his finals when his father became ill so he had to return to Liverpool to look after his father’s practice while he recovered. As he missed his exams he took the conjoint diploma LRCP MRCS.

Liverpool

After spending some time in Paris, Hugh Owen Thomas returned to Liverpool in 1858 and joined his father’s practice. A little friction developed between them as the educated son returned home with new ideas. Evan Thomas retired to Anglesey 2 years later.

What sort of place was Liverpool in 1858? The first steam ships came in 1815 and were crossing the Atlantic in 1819. The first railway in the world was opened between Liverpool and Manchester in 1830. Consequently, the traffic through the docks was immense. With this came a vast number of labourers and dockers. However, there was no corresponding growth in the medical services to deal with injuries and other diseases such as tuberculosis, which was rife in the city.

Therefore Hugh Owen Thomas was in a very special position to gain vast experience of injuries and skeletal tuberculosis.

Hugh Owen Thomas then moved to 11 Nelson Street where he practised for the rest of his days. These are the lathes in Nelson Street where he had a workshop, a full time blacksmith, saddler and other men who made bandages and plasters for him. He also had a house in nearby Hardy Street which was an 8 bedded private hospital.

By now he was the medical officer to 28 trade unions and had a very busy practice. His motto was “On”. He was a small, frail man but full of energy. His only holidays were 3 days a year when he visited his mother’s grave in Anglesey. Otherwise he worked 7 days a week for over 30 years. He said of himself “There isn’t a happier man in England than I am. I find my enjoyment in my work and my home and am never happier than here with all of you about and plenty of work. I would much prefer a short useful life to a long lazy one. I hope to die in harness”, which he did.

He was a small, slight, pale figure, only a few inches over five feet, with a moustache and beard, wearing thick glasses, always in a black frock coat buttoned up to the chin, a peaked sailor's cap pulled down over one eye so that he very much resembled the Captain Kettle of fiction, and always with a cigarette in his mouth. He worked under immense pressure for thirty years, every day for seven days a week with not a single holiday, entering whole-heartedly with his frail body and anxious mind into his patients' troubles and sparing no effort in his struggles on their behalf. The only occasions when he left his house, other than on professional errands, were the three times each year when he visited his mother's grave.

At five or six in the morning he began his rounds in the high phaeton, built in his own workshop to his own design, painted scarlet so that it resembled a fire-engine, carrying at night a flaming torch at each corner, and pulled by a splendid pair of horses. In this carriage, seated high above his tandem team, he raced up and down the streets of Liverpool for two or three hours before breakfast, often calling on patients in their homes so early as to be mistaken for the milkman. If the bandages had been meddled with Thomas stormed at the penitent patient, re-applied the bandage, and sealed it with a blob of wax and the signet ring from his finger carrying the initials н.о.т. Breakfast was a hurried meal, and then from nine to two he was in his consulting room, prescribing, dressing, reducing fractures and dislocations for thirty or forty patients whom he examined with rapid and gentle accuracy. No anaesthetic was ever used, and no outside aid was ever needed to provide the splints which were made on the premises by Thomas's own blacksmith and saddler.

No matter what the site of his disease, the patient could be sure of returning home in an hour with the appropriate well-fitting splint. In the afternoon there were more visits and then operations at his private hospital. The records show that an average week provided sixteen or twenty major limb fractures, several of them compound, several cases of obstruction, and cases of joint disease and deformity, all in addition to the enormous general medical and surgical practice. There were some eighty surgery patients daily and as many home visits, and all were treated by Thomas himself. Sunday was the famous free clinic day when hundreds of patients from all over the countryside besieged Nelson Street in the morning, filling the house to overflowing and the surrounding streets with carriages and invalid chairs.

On one occasion 146 patients were seen in the surgery and 16 visited in their homes. It was a great scene, with something of the atmosphere of a religious pilgrimage, and surgeons who were present never ceased talking of what they had witnessed, for Thomas was years ahead of his time and the results he could show in his treatment of fractures and tuberculous arthritis seemed little less than miraculous. He believed in always making patients pay something, however small, to preserve their self-respect and value their treatment; but his wife would sometimes send them home in a cab at his expense and maintain them afterwards from his own pocket. This is a first-rate biography of a remarkable man who may well be called the founder of modern orthopaedic surgery. It is unusually well illustrated. It should be read by all the modern generation of orthopaedic surgeons and will greatly interest a far wider field.

.jpeg?width=280&height=180&name=images%20(28).jpeg)

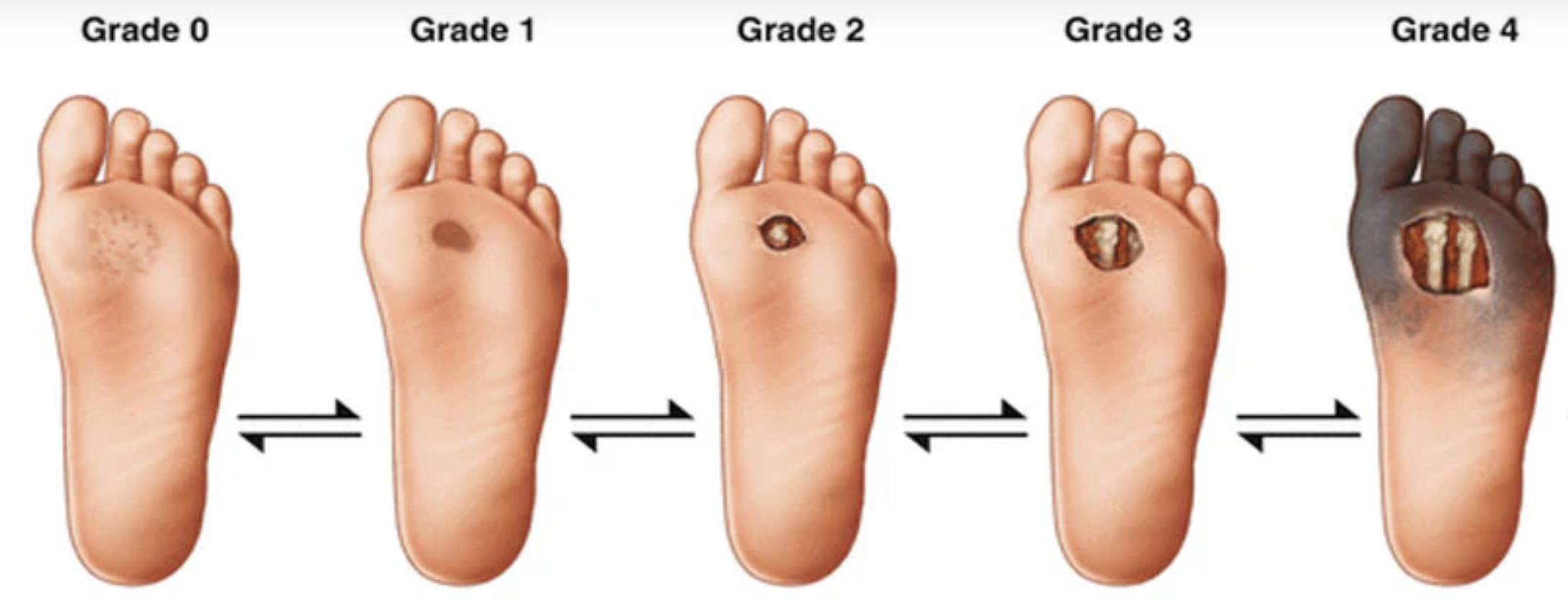

The Thomas’s was invented in Nelson Street and used to treat tuberculosis by prolonged and uninterrupted rest. The principle had been established by his father and refined by Hugh Owen Thomas.

Hugh Owen Thomas apparently went to only 4 medical meetings in his life. He did, however, receive may invitations including 2 to annual meetings of the BMA to demonstrate his method of using his splint in 1878 and 1879 but he declined as he was probably too busy. Therefore in 1883 part of the BMA meeting was held in 11 Nelson Street, Liverpool where 30 patients in various stages of tuberculosis of the hip were shown. Imaging the reaction of the audience when he removed his splint from a patient who had been treated for many, many months with the splint and full motion was seen in the joint. The alternative was surgical excision of the joint.

Robert Jones and Hugh Owen Thomas

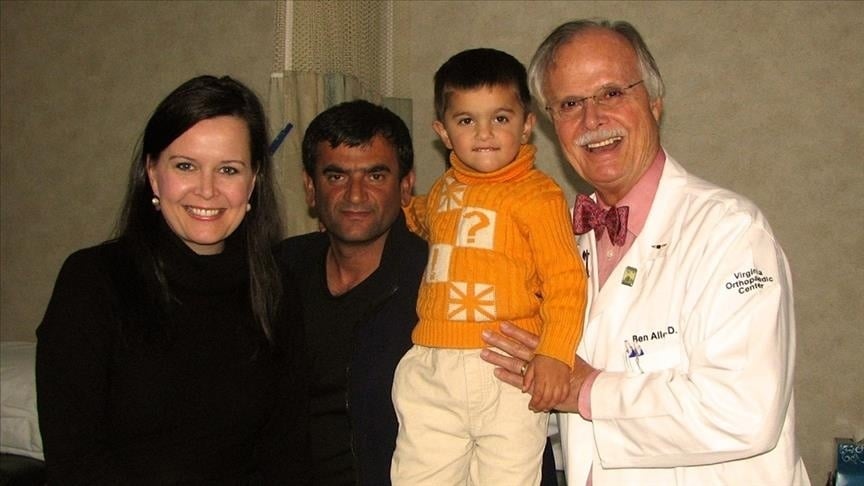

Robert Jones came from Rhyl and was a nephew of Hugh Owen Thomas. As he was orphaned at a young age, he was brought up in Nelson Street by his uncle. He later established the Robert Jones and Agnes Hunt Orthopaedic Hospital in Gobowen, which still plays an important role in the training of our young surgeons today. One of Robert Jones’s attributes was his organising ability. He was responsible for setting up the first accident service to deal with those injured when building the Manchester ship canal. During the Great War he was called up as a Brigadier and charged with the evacuation and treatment of those injured in the trenches. At that time the mortality from a femoral fracture, usually an open injury, was 80%. Robert Jones utilised the Thomas’s splint for the evacuation of the injured. The effect was astounding; the mortality fell from 80% to 20%.

.jpg?width=210&height=300&name=bs14%20(1).jpg)

A patient with a tuberculous hip

.jpg?width=216&height=300&name=bs15%20(1).jpg)

Robert Jones and Hugh Owen Thomas

At his funeral in Liverpool in 1891, in front of crowds of mourners the clergyman described Hugh Owen Thomas as a driven man: ‘Work was his meat and drink; work of the most practical and urgent kind. He never spared himself. He used up every bit of life that was in him. … Each day he wrought with his might as though it was his last and only chance.