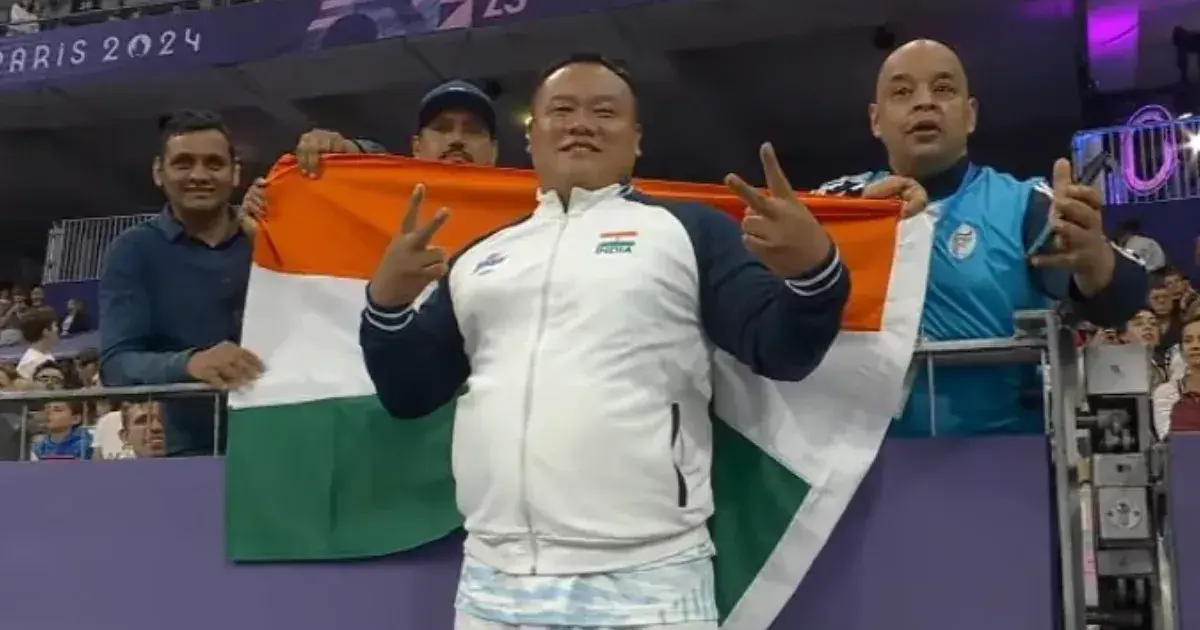

A group of para-athletes were gathered in a circle close to the entry gate of the JN Stadium in Chennai. Paris Paralympic Games medallist Hokato Sema was one of them. There were about seven-eight of them chatting about life and sport while waiting for their turn to compete. ‘Services’ was written on their back. Not too long ago, there used to be just one or two in nationals.

Army Paralympic Node (APN) officer in charge Nitten Mehta was with the team. On the sidelines of the nationals, Mehta spoke about the journey of this unique place — the APN. He still remembers incidents that are enough to bring tears to the eyes. He animatedly narrates it with a lot of passion. Mehta lost three fingers and hurt his right hand from splinters in a blast.

One such story goes like this. One soldier had come to his centre some time ago. Nitten did not want to name any para-athlete because for him, all athletes are the same. He was a double amputee and was walking with two sticks. He looked crestfallen and shattered, as if the world came crashing down. Mehta saw the transformation in three months. “He walked without sticks,” he recollects. “Progress in sport is one thing. But being able to help somebody to do away with walking sticks and helping him be independent is also a big satisfaction.”

Mehta shares some light on the centre. “The aim behind the APN was to give physically-impaired soldiers a second innings or a second chance to serve the nation or the organization. This time to excel in para-sports.”

The centre started with 10 athletes and the 2018 Asian Games was a big landmark as para-athletes from the centre won five medals. “Tokyo Olympics was the first time an athlete from APN qualified for the Paralympics,” says Mehta, adding 2023 and 2024 have been watershed years for APN. “In 2023, we won seven medals at the Hangzhou Asian Games with one world record and one Asian record,” he says. “In 2024, four athletes from the APN qualified for the Paralympics, and it was after 52 years when Muralikant Petkar medalled at the Paralympics that another Indian Army person won a medal.” said Sema.

The APN doesn’t have to go far to scout. The Artificial Limb Centre at Pune serves as a scouting place. “Our coaches and our talent scouting team go there regularly, interact with the athletes who are undergoing treatment after losing a limb, and motivate them to join para-sports,” explains Mehta. “Since sport is not only a rehab, it is a chance to do something with life, give them an aim, give them a course of life that is healthy, which is to shine for the nation.”

However, the officials have their challenges as well. “The biggest step for an athlete is his willingness to participate in para sports and train for it. Because all these athletes were all normal people leading a normal life before a tragedy. They are at the rock bottom. From there, they rise again."

Mehta explains how they go about inducting athletes. “Once a person comes to us, we see his form, his physical ability and his capability. Then we choose the appropriate sport and event for him. Then we train him for that particular sport. We have got adequate coaches and support staff.”

Mehta says with the support of the Mission Olympic Wing of the Army and the Ministry of Social Justice, the APN has started to develop further. “We don't have a track, but now with the support of the Minister of Social Justice and Empowerment, we are creating some synthetic track, sports facility and a strength and conditioning hall in phase one,” he says. He believes that the para-athletes from the centre should win some eight medals at the LA Paralympics. “Before that there's the Commonwealth, there is the Asian Games. The Asian Games should be a double digit podium finish for the APN in 2026.

"We train in seven different sports: para-athletics, para swimming, para-archery, para-canoe kayaking, para rowing, para-shooting. We have just ventured into paratriathlon a couple of years ago and we are still debating about wheelchair fencing.” Initially, APN had four athletes in nationals and now they have come with 17 athletes. "We go swimming with a team of seven to nine swimmers and we come back with 19 to 20 medals because in swimming, each person is allowed three events. We have around seven to eight shooters."

A challenge Mehta and his men face is motivating the para athletes and getting them back to shape. “One has to realise that a person may be willing but due to the sedimentary life that he's been living post-injury, his body doesn't allow him to work out or train as a competitive athlete,” he says. “You have to undo everything and then start from the beginning.” Not all injured soldiers don’t end up in APN, either. “We take feedback from the coaches and evaluate everything and if we feel that despite all efforts a person will not be able to be part of the competitive sports then we have to send him back.”

He says that the Paralympic Committee of India too has been giving them immense support in terms of classification of our athletes on priority basis.

Mehta speaks of another para athlete. “Another story is about an able-bodied 1500m national participant who came fourth. He was in ASI and went on leave after the nationals. He was helping his father in the farms in his village. He had an accident and lost his hand from the wrist. This happened in December 2022. He worked hard, changed from 1500m to 400m in Para and represented India in the Asian Games.”

There are probably 48 different stories of 48 para-athletes training in different sports at the APN. All of them may not medal. But one thing is sure, sports have shown them direction, given them opportunities to fulfil their dreams.