Hanan, who is three years old, lost both her legs in an Israeli air strike that killed her mother last month. Her sister, Misk, 18 months old, lost her left leg – she had just started learning how to walk. They are only two of more than 4,000 children left without at least one limb since Israel waged war on Gaza last October.

“The situation is heartbreaking – Misk had just learnt to walk and now she can’t,” said Shifaa Al Dogee, who now cares for her two nieces. Hanan, who is too young to understand her condition, keeps asking about her legs.

“She asks why other children have legs but she doesn’t,” Mrs Al Dogee told The National. “I can’t find the words to explain it to her. When they ask about their mother I tell them she’s coming, but they’ve started to lose faith in my answers. What should I say when she asks who took her legs?”

The Ministry of Health in Gaza estimates more than 10,000 Palestinians have lost at least one limb since the start of the war a year ago, including at least 4,000 children. The World Health Organisation estimates the number of amputations in the Gaza Strip at between 3,105 and 4,050.

Severe limb injuries, estimated to be between 13,455 to 17,550, are the main driver of the need for rehabilitation, said the World Health Organisation. A surge in spinal cord, traumatic brain and major burn injuries contribute to the overall number of life-changing conditions, according to the UN agency.

Sahar, 8, who lives in Jabalia camp in northern Gaza, lost her left leg in a bombing that also claimed the life of her mother in April. “The loss of my wife was incredibly difficult,” her father Saqr Wadi told The National. “But seeing my daughter lose her leg was even harder.

“Sahar was always so full of life – running, playing, laughing – and now she’s confined. Sometimes, I carry her outside just to give her a change of scenery.”

His two sons were also injured in the attack, but their wounds were minor. In Gaza, many children are bearing the physical and emotional scars of a grinding year of war. Sahar’s injury has left her emotionally devastated.

“She’s not the same joyful child she once was,” her father said. “Now, she mostly talks about death and war, all she wishes for is to stand on her feet again.”

The family faces immense challenges in buying painkillers and medicine under the Israeli blockade. “We’ve applied for travel permits to get her proper treatment but no one has responded.”

Mr Wadi’s greatest wish is for Sahar to receive a prosthetic leg. “I just want her to walk again like other children. She loved karate and going to the club but now she’s deprived of all that.”

New reality

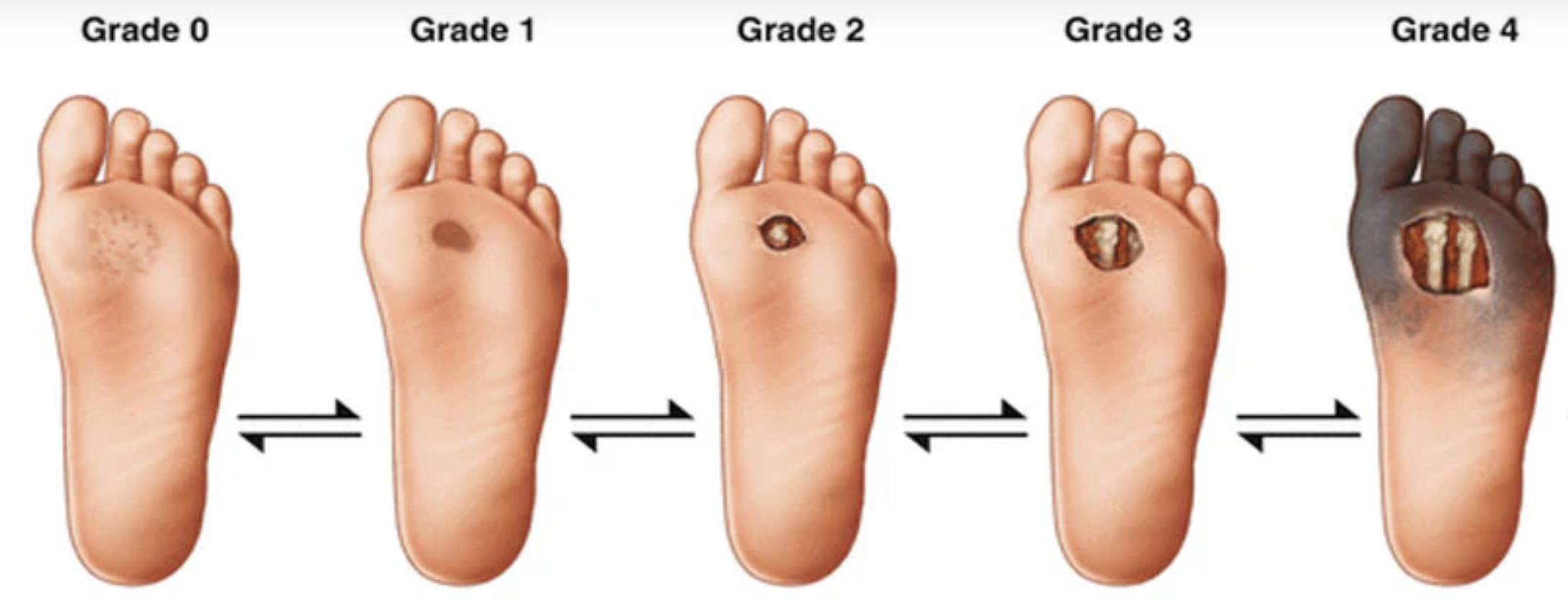

Dr Mohammed Shaheen, an orthopaedic surgeon at Al Aqsa Martyrs Hospital in Deir Al Balah, said that amputations in Gaza are often a result of deep tissue injuries.

“We make the decision to amputate when the limb is beyond saving due to infection, loss of arteries, deep tissue damage or bone loss. When patients arrive with an already amputated limb, they usually understand. But when we have to decide on amputation, convincing them is difficult.”

Dr Shaheen estimates there are about 10 amputations daily across Gaza, with three taking place at Al Aqsa Martyrs Hospital alone. It takes a team of specialists, including orthopaedic surgeons, vascular surgeons, physical therapists and mental health professionals, to prepare an amputee for their new reality.

Arafat Abu Mashaikh, head of the Mental Health Department at Al Aqsa Martyrs Hospital, highlighted the deep psychological wounds left by amputations.

“Losing a limb, changing body appearance and the inability to perform daily activities causes immense psychological distress, he told The National. “It’s a journey that begins with denial and only ends with acceptance, and many never fully reach that point.”

To compound matters, Gaza's lack of rehabilitation centres, wheelchairs and crutches makes it harder for amputees to adjust to their new circumstances.

“I often face the same heartbreaking question from children: 'Will my leg grow back?’ And I can’t answer them because they don’t yet understand the reality of their situation,” Dr Abu Mashaikh said.

With no prosthetic centres or sufficient mental health facilities in Gaza, he said there is a great need for more mental health professionals to help amputees cope. “Even our society needs to become more accepting of these cases,” he said.