A team of Italian researchers has developed the first-ever prosthetic hand controlled by magnets, a breakthrough they say could give people more dexterity compared to existing technology.

Scientists at the Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies in Pisa, Italy, shared the new design in a study published Wednesday in Science Robotics.

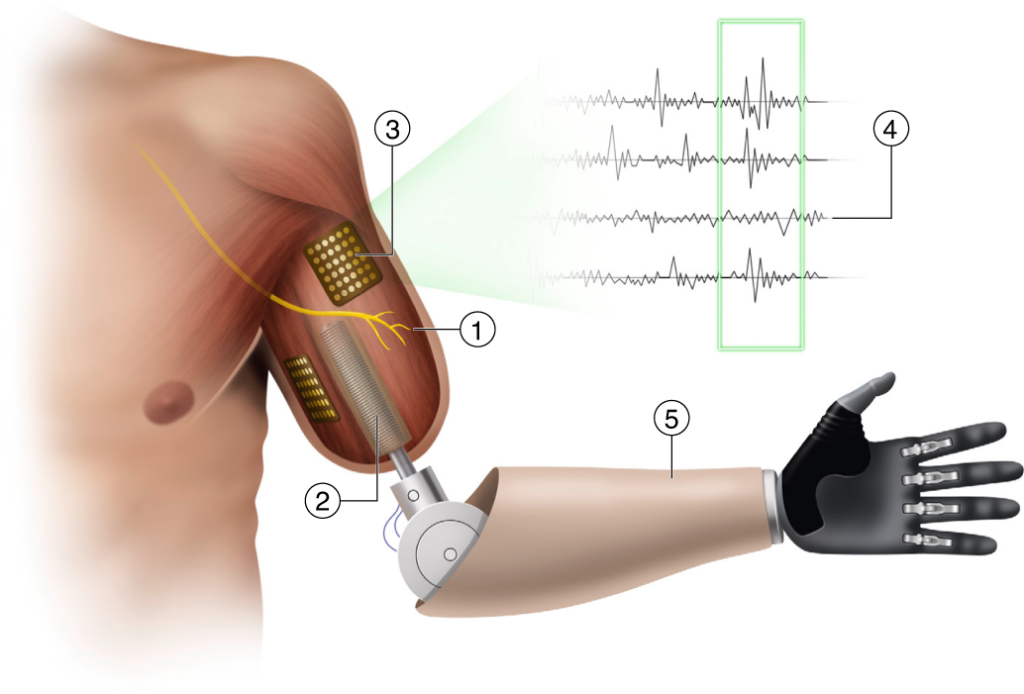

They implanted tiny magnets in the muscles of a man's residual limb, allowing sensors in a prosthetic socket to detect muscle movements as the magnets change position. The socket then sends signals to the robotic hand telling it to move, letting the amputee control the prosthetic like their actual hand. The researchers call this method myokinetic control.

In a six-week-long case study, a 34-year-old Italian man named Daniel who'd lost his left hand five months before used the robotic hand to do a range of everyday tasks, including opening a jar, using a screwdriver and cutting with a knife. Daniel could also control the force of his grip while handling fragile objects like an egg and a plastic glass.

“This system allowed me to recover lost sensations and emotions: It feels like I'm moving my own hand,” Daniel said in a statement.

The researchers tested two types of myokinetic control — one where the prosthetic was controlled directly by changes in the magnets' position, and another where machine learning was used to train the interface to recognize patterns. They found the magnet-controlled robotic hand worked as well as current state-of-the-art technology, called myoelectric control, which uses electrical signals from nerve impulses to operate robotic limbs.

In the study, the scientists placed magnets on the surface of the muscles to minimize invasiveness. Implanting the magnets deeper could make the technology even more effective, first author Marta Gherardini told Courthouse News Service.

Since the technique measures muscle velocity directly, it could give people better control of how forcefully they move the limb, Gherardini said — along with more control of finer movements, like moving individual fingers, which isn't possible now.

Only certain types of patients can benefit from this kind of prosthesis for now. The study's authors say optimal candidates for future testing would be people with a recent amputation, without muscle atrophy or loss of nerve supply, who have a relatively long stump.

However, the scientists hope new surgical methods to improve muscle mobility in residual limbs will one day increase the number of people who can benefit from these types of prostheses.

The researchers are working on expanding myokinetic control for use in a wider range of amputations, such as lower limbs.