As someone who uses additive manufacturing daily in healthcare, I was particularly interested in the AMS medical track. The track did not disappoint. I'll begin with a story shared by Amy Alexander, a Biomedical Engineer from Mayo Clinic.

In 1915, the Mayo brothers, Drs. William and Charles Mayo, recognised that skilled makers—craftsmen and engineers—played a crucial role in advancing medicine. At the Mayo Clinic, they collaborated with artisans who designed and built custom medical devices and instruments, improving patient care by tailoring solutions to specific challenges. This partnership set a precedent for integrating technical expertise into healthcare, a practice that continues to evolve with modern manufacturing technologies.

Alexander specialises in developing point-of-care solutions using additive manufacturing. Her work focuses on creating 3D printed medical tools and devices that clinicians can use immediately at the bedside or operating room. She has also helped integrate additive manufacturing into hospital workflows, ensuring that customised medical solutions are available when needed. Whether a surgeon requires a patient-specific anatomical model for preoperative planning or a physician needs a custom-fitted splint for a trauma patient, Alexander's expertise in 3D printing at the point of care has streamlined the process.

Her approach reduces lead times for critical medical devices, eliminates reliance on external suppliers, and allows healthcare professionals to design and produce patient-specific solutions on demand. This shift from centralised manufacturing to localised, on-site production is transforming medical care, making it faster, more personalized, and cost-effective.

A key factor driving the adoption of additive manufacturing in medicine is peer pressure and fear of missing out (FOMO). As hospitals and research institutions successfully integrate medical modelling into their workflows, others follow. Seeing competitors and colleagues achieve better patient outcomes through 3D printed models encourages broader adoption.

Alfred Griffin, CEO of LightForce, shared another compelling story. In 1946, a dentist pioneered the concept of the clear dental aligner. While clinically sound, his idea lacked a viable production method. Without a way to scale, the innovation remained unrealised—until advances in manufacturing, specifically additive manufacturing, enabled the creation of customised aligners at scale. This example illustrates a recurring challenge in medical innovation: having the right idea but lacking the means to bring it to life.

As John Barnes, Founder of Barnes Global Advisors, puts it, "Adapt, overcome, and persevere." This mindset is essential for innovators facing technological, financial, and regulatory hurdles. The ability to push through challenges has led to groundbreaking applications in medicine.

Brigitte de Vet-Veithen, CEO of Materialise, emphasised that education and public relations also play a critical role. Many healthcare professionals remain unaware of the potential of additive manufacturing, viewing it as a niche tool. Conferences, industry publications, and training programs help dispel misconceptions by showcasing real-world successes. Tactile demonstration is also a strong driver of adoption—surgeons and oncologists who hold and examine 3D printed anatomical models immediately recognise their value. Unlike imaging techniques, these models provide a physical representation of a patient's anatomy, improving surgical planning, enhancing communication with patients, and reducing uncertainty in complex procedures.

Despite its promise, the adoption of additive manufacturing in medicine is often hindered by financial constraints. Dr. Jenny Chen, a radiologist and CEO of 3DHEALS, has emphasised funding strategies to overcome these obstacles, including collaborative funding models where hospitals, universities, and private industry share resources. Open-source medical innovation allows researchers and engineers to contribute collectively to new developments, while public and nonprofit grants aim to accelerate adoption in areas with high potential for patient impact. By working around funding limitations, medical innovators can bring technologies to patients more quickly.

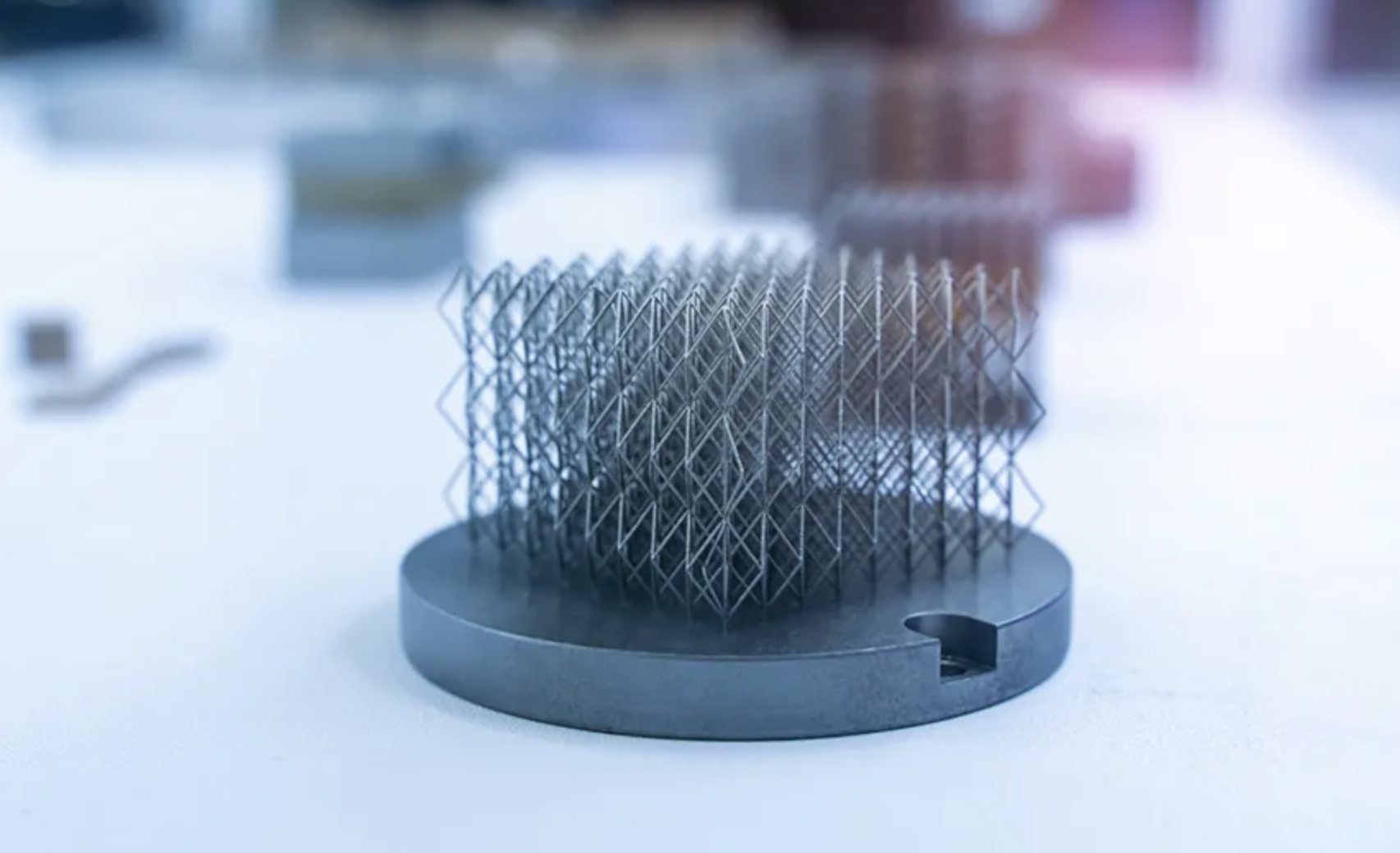

One of the most promising applications of additive manufacturing in medicine is medical modelling for surgical planning. Before a complex operation, surgeons can use patient-specific 3D printed models to practice procedures and develop precise approaches. These models, derived from high-resolution imaging, allow for better visualisation of anatomical structures, leading to shorter operating times, fewer complications, and improved patient outcomes.

Another critical application is in cancer treatment positioning devices, particularly in radiation oncology. Rajan Patel and his team at Kallisio have developed custom-fitted, 3D printed positioning mouth guards for patients undergoing radiation therapy for head and neck cancers. These devices secure the tongue and jaw in an optimal position, ensuring radiation is delivered accurately while protecting healthy tissue.

For instance, a patient receiving tongue or throat cancer radiation may use a 3D printed mouthguard designed to position the tongue away from high-dose radiation zones. By stabilising the tongue and maintaining placement, these devices help reduce unintended radiation exposure, lower side effects, and improve treatment outcomes. Unlike traditional mouth guards, which often require frequent adjustments, these 3D printed versions are tailored to each patient's anatomy, ensuring a secure and repeatable fit throughout treatment. This precision enhances both treatment effectiveness and patient comfort.

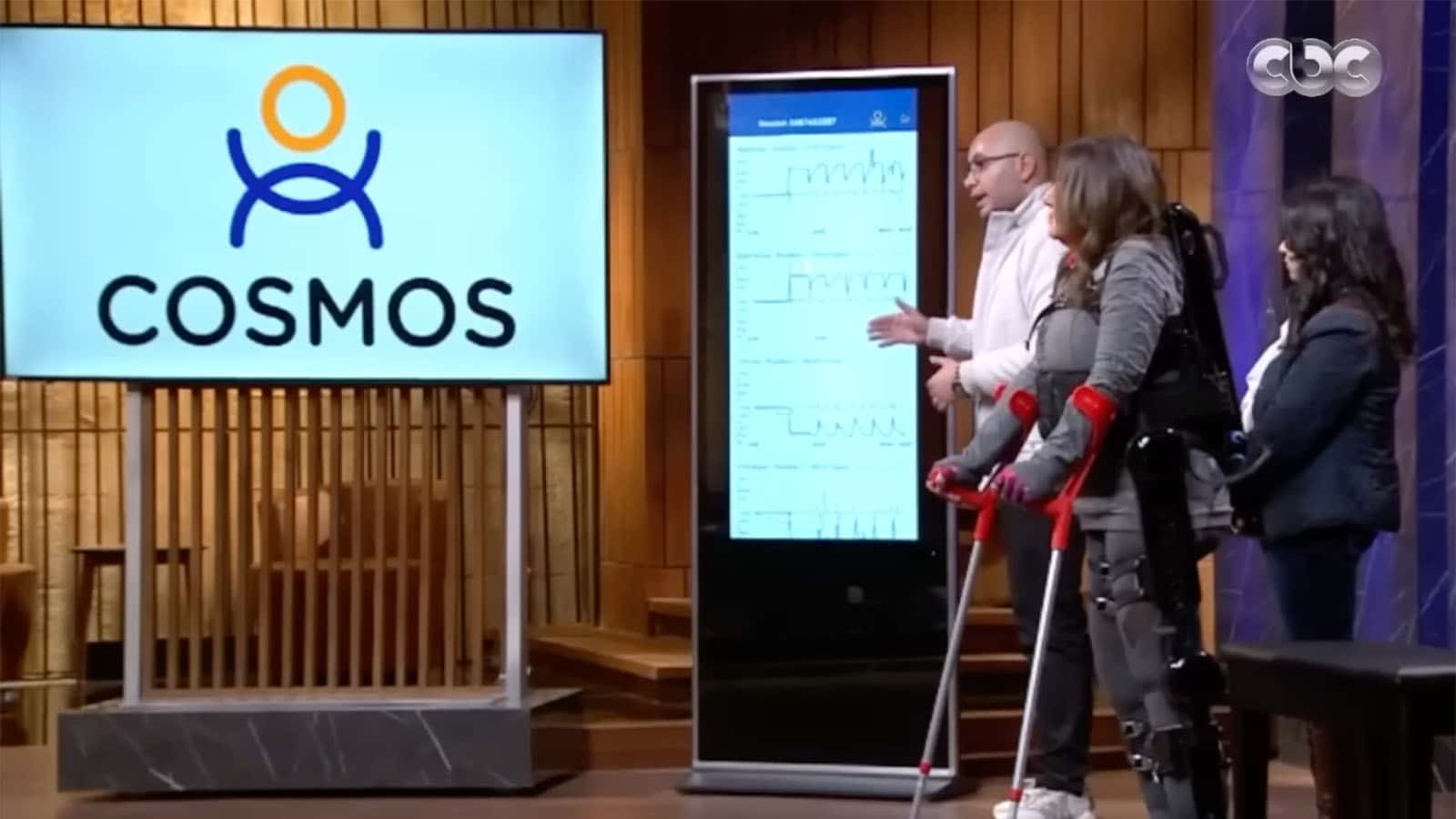

Additive manufacturing is also transforming the world of assistive devices, a focus of Satish Mistra. His work in developing low-cost, customisable 3D printed assistive tools has expanded access for individuals in underserved communities, where such devices would otherwise remain out of reach.

Mistra has emphasised that a prosthesis is not just about mobility—it is about dignity and opportunity. A well-fitted prosthesis allows people to regain independence, perform daily tasks, and return to work. One of the challenges in traditionally fabricated prostheses is cost and accessibility. Many patients cannot afford prostheses, and the fitting process can be arduous. With 3D printing, prostheses can be produced quickly, more affordably, and tailored to individual needs—eliminating logistical hurdles such as shipping, taxes, and customs, which can account for up to one-third of the total cost of a device.

The future of medicine is being shaped by additive manufacturing, as it continues to enhance surgical planning, cancer treatment, and prosthetics. The ability to create patient-specific solutions is improving outcomes, reducing costs, and expanding access to care. With AMS providing a platform for leaders to come together and share ideas, I leave encouraged that additive manufacturing is no longer an emerging technology—it is a tool actively transforming patient care for the better.

The question is no longer whether additive manufacturing will change medicine, but how quickly it can be fully embraced. With the right champions, collaborations, and investments, the future of healthcare is being printed—layer by layer.