Modern medicine has existed for a relatively short period of human history. Before the biological basis of illness and disease was understood, it was attributed primarily to supernatural forces, often with the assumption that a deviation from normal function indicated divine punishment, and preservation or healing indicated divine blessing.

Ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and other societies attributed various aspects of health and behavior to four humors (fluids) within the body. In the second century, Galen, the Greek physician often considered the father of modern medicine, systematized this theory.1 Humoral theory formed the basis of understanding health until the 1600s, and remnants of it persist in popular contemporary personality assessments.1 As wrong as this theory was, it marked a significant shift from viewing disease as supernatural, to viewing it as something arising from natural and observable causes.1

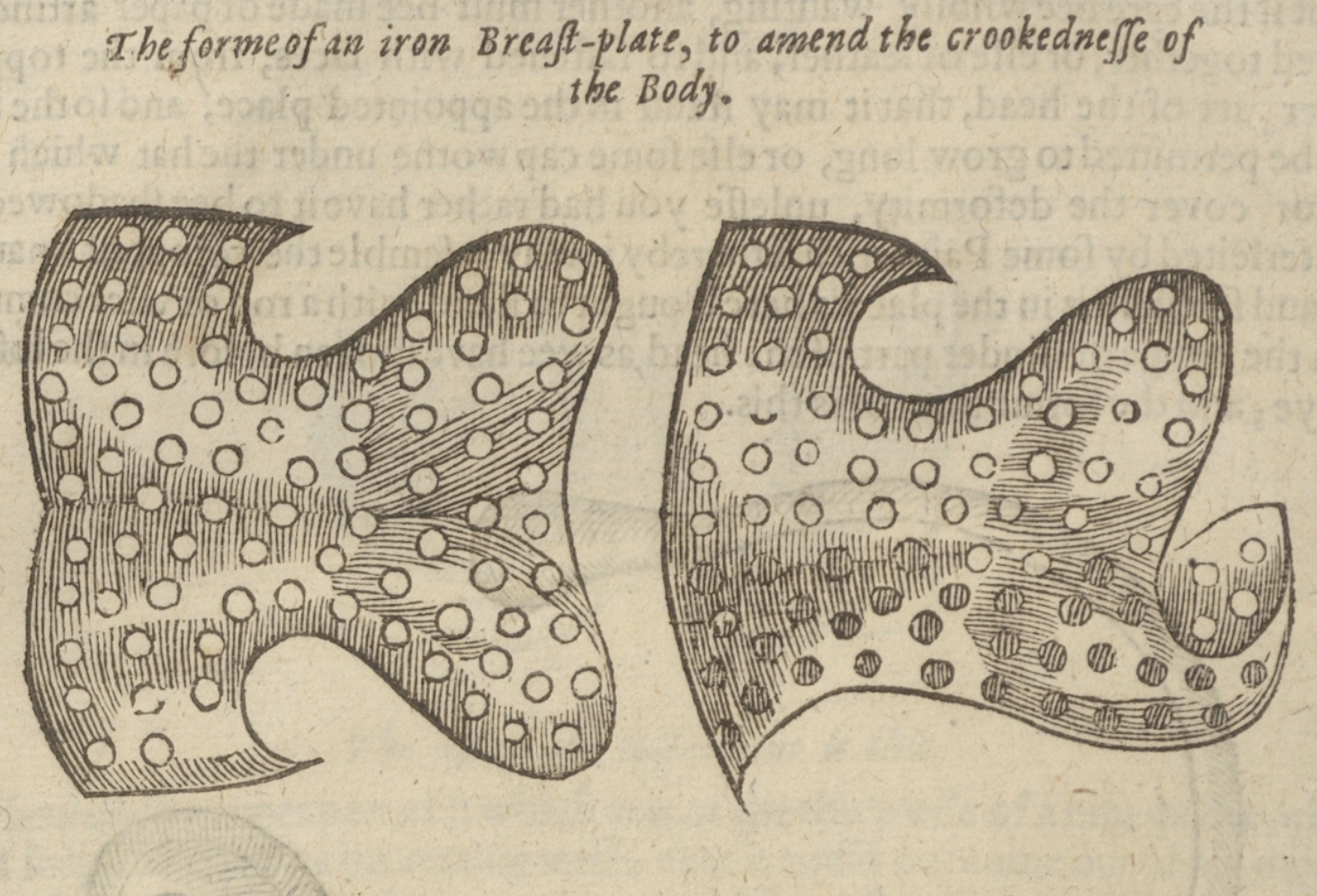

As medical science progressed, more localized causes of disease were discovered.1 An anatomy text published by Andreas Vesalius in 1543 supported the view that the “function of the body is related to its structure.”1 In 1761, an Italian physician, Giovanni Morgagni, compared individuals’ symptoms prior to death with the condition of their organs during autopsy and described how organ changes were responsible for illness and death.1 Further advancement in the understanding of tissues, cells, and germs during the 1800s led to a more refined understanding of the causes of disease, and germ theory was “indisputably established in Western medicine” by 1900.1 The study of genes has led to a still deeper understanding of health and illness.

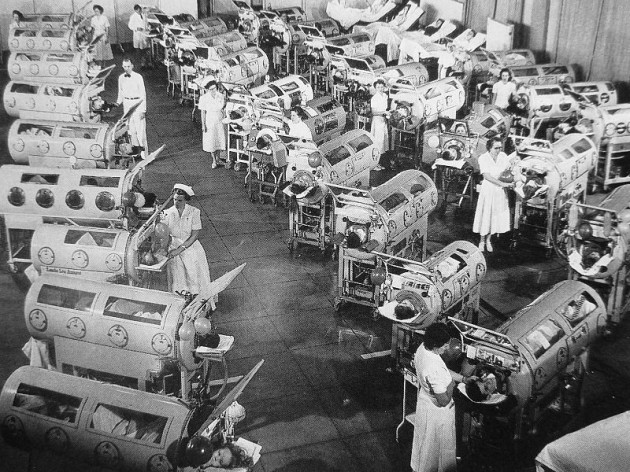

The increase in scientific knowledge has resulted in medical care focusing primarily on identifying and addressing the biological contributors to disease. Disease represents a problem to be fixed, and without question the progress of modern medicine in providing cures and improving quality of life has been impressive.

Placebos and Nocebos

The modern commitment to understanding illness as a biological and chemical phenomenon includes the understanding that, however poorly understood, there is a connection between nonbiomedical factors and biological consequences, as well as how disease impacts the experience of an individual person. For example, “Expectations can impact the course of treatment by affecting the psychological and physiological responses to that treatment.”2 A placebo can cause “improvement in a patient’s condition because of the factors associated with the patient’s perception of the intervention.”2

The nocebo effect, on the other hand, describes a negative outcome that “occurs due to a belief that the intervention will cause harm.”3 “Both placebo and nocebo effects…can induce measurable changes in the body.”2 This phenomenon is so widely accepted that the gold standard for validating treatment is the “randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled” trial.2 The placebo effect highlights the mysterious interrelationship between biological/chemical and psychological/sociological factors and can inform our understanding of how to effectively address our patients’ experiences with illness, disease, and disability.

The Biopsychosocial Model

In 1977, George Engel, MD, a professor of psychiatry and medicine at the University of Rochester School of Medicine, published an article addressing the limitations of the biomedical model of disease.4 (A model is “a belief system utilized to explain natural phenomena, to make sense out of what is puzzling or disturbing.”4) In the biomedical model, “demonstration of the specific biochemical deviation is generally regarded as a specific diagnostic criterion for the disease.”4 He pointed out that “the boundaries between health and disease, between well and sick, are far from clear…for they are diffused by cultural, social, and psychological considerations” and emphasized that the ways physicians conceptualize disease “determine what are considered the proper boundaries of professional responsibility and how they influence attitudes toward and behavior with patients.”4 He was concerned about “the logical inference that since ‘disease’ is defined in terms of somatic parameters, physicians need not be concerned with psychosocial issues which lie outside medicine’s responsibility and authority….”4

Claiming that “a medical model must also take into account the patient, the social context in which he lives, and the complementary system devised by society to deal with the disruptive effects of illness…,” Engel proposed a biopsychosocial model, which “would make it possible to explain why some individuals experience as ‘illness’ conditions which others regard merely as ‘problems of living….’”4 This is particularly relevant to our understanding of disability, which involves a diagnosis as well as the experiences of individuals who often live with the consequences of it for extended periods of time. Individuals may not have a disease or medical diagnosis following a traumatic amputation, but many other factors contribute to their “problems of living” and their ability to function in everyday life. It is also common for individuals with similar diseases or disabilities to function at different levels due to nonbiological factors. An individual’s tolerance of pain and his or her level of motivation may not be directly related to a medical diagnosis but can be the defining factors in his or her ability to participate in activities of daily living.

Models of Disability

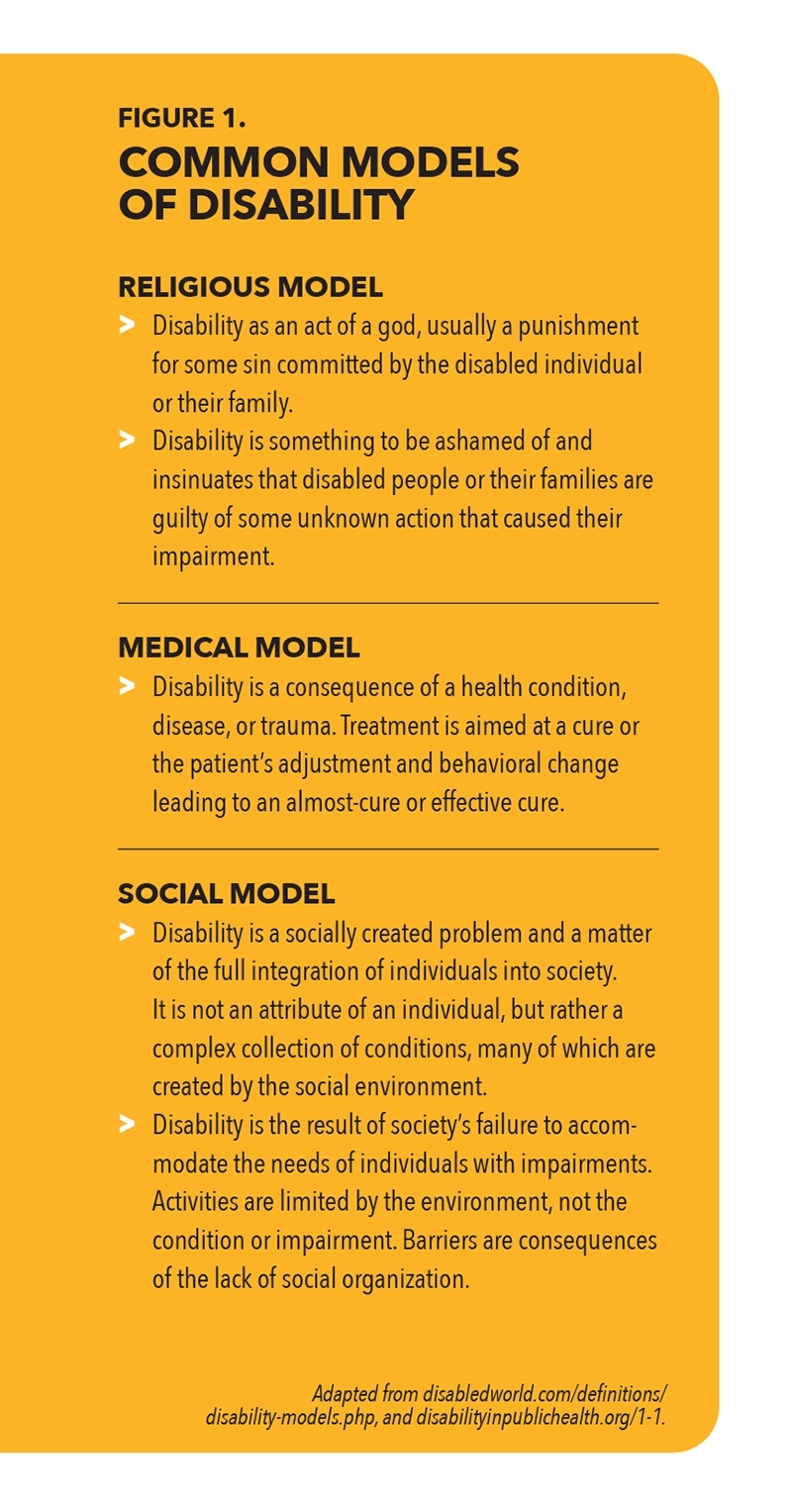

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), “disability is an umbrella term for impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions. It denotes the negative aspects of the interaction between a person’s health condition(s) and that individual’s contextual factors (environmental and personal factors).”5 The website DisabledWorld.com lists 20 models of disability, and Figure 1 describes several common models.6 Disability models are rarely understood to exclude any other factors but instead emphasize different factors that contribute to health, disease, and disability.

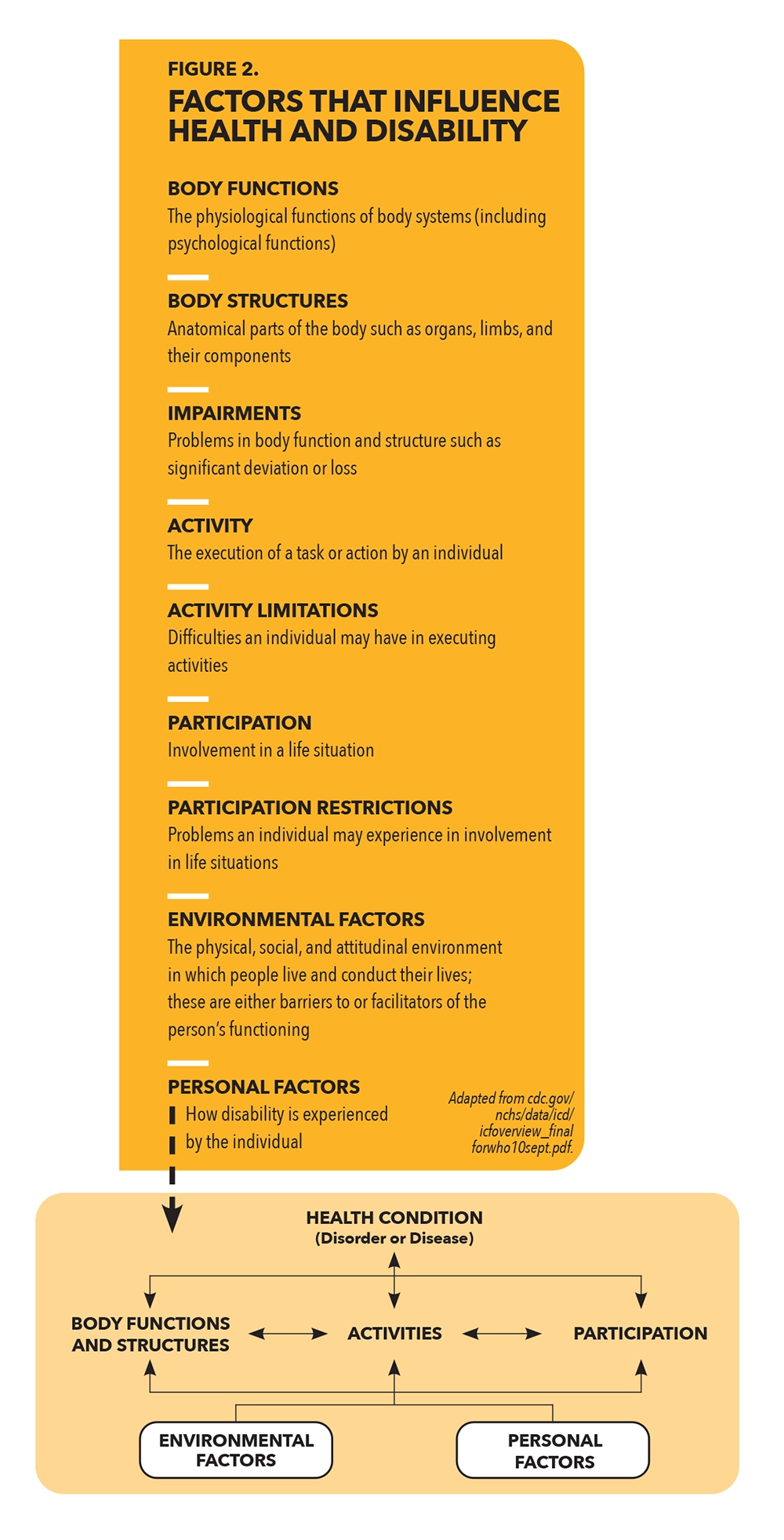

In 2001, the WHO endorsed the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) “as the international standard to describe and measure health and disability.”7 This biopsychosocial model identifies key factors that influence health and disability in a way that acknowledges how each factor can influence the other (Figure 2).

The interrelations between these contributing factors can be clarified with a familiar example. A stroke results in specific damage to neurological structures, which impacts the function of muscles and limbs (body structure and function). Resulting impairments (such as muscle weakness) can affect walking ability (activity). This activity limitation may create barriers to attending social events (participation restriction). Wheelchair accessibility and family and friends who encourage and support involvement (environmental factors) facilitate participation in social activities. A different individual with equivalent physical impairment will experience many more limitations (and disability) if accessible infrastructure is not available, friends and family are embarrassed to be seen in public with him or her, and ineffective coping skills exacerbate anxiety and depression (personal factors). Each of these factors are relevant to the patient’s medical and orthotic care and should be considered by practitioners who view their patient as a person rather than a diagnosis.

Application to O&P

There are several ways that the biopsychosocial model can be applied in O&P care in practical ways.

The Practitioner/Patient Relationship

Engel points out that “the behavior of the physician and the relationship between patient and physician powerfully influence therapeutic outcome for better or for worse….”4 Medical care “is limited by the physician’s ability to influence and modify the patient’s behavior in directions concordant with health needs.”4 Accurate medical advice and an appropriately fitting device will have less positive impact if patients distrust their practitioners and are unconvinced of their knowledge and skill. Evidence-based interpersonal skills (such as motivational interviewing), which lie outside of the biomedical framework, can strengthen the therapeutic alliance between the practitioner and patient and improve the effectiveness of treatment.

Spirituality and Meaning

“Spirituality is the aspect of humanity that refers to the way individuals seek and express meaning and purpose, and the way they experience their connectedness to the moment, to self, to others, to nature, and to the significant or sacred.”8 Research by the Pew Research Center found that family and religious faith were cited most frequently by Americans as the most important source of meaning and fulfillment in their lives.9 These realities are psychological and sociological, not biological, and can be addressed within the biopsychosocial perspective.

Research published in 2000 investigated “whether people consider that there are any beneficial outcomes after amputation.”10 Some of the benefits identified by the subjects related to practical, functional benefits from amputation and prosthesis use, such as pain reduction and independent mobility. Other themes included character building, attitude of life, coping abilities, and “meeting people they would not have met but for the amputation.”10 These benefits are psychological and sociological, not biological, but impact physical function and disability. The researchers found that “finding positive meaning was significantly associated with more favorable physical capabilities and health ratings, lower levels of Athletic Activity Restriction and higher levels of Adjustment to Limitation.”10

Given that more than 80 percent of Americans describe themselves as religious or spiritual, and faith and religion are a common source of meaning, O&P practitioners cannot afford to ignore this factor in the lived experiences of their patients.11 Agreement with patients’ beliefs and practices is not required to understand how they impact patients’ experiences and decisions. Additionally, “religious persons report greater well-being, more purpose and meaning in life, greater hope, and greater self-esteem and are more likely to be optimistic. Diagnoses of mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression are also less common among religious people.”11 Practitioners can support decisions that improve patients’ lives by affirming their spirituality.

Pain and Suffering

Pain, a common indicator of pathology in the biological system, is a completely subjective experience. Practitioners rely on patient reports of the degree and nature of pain, and many nonbiological factors influence patients’ experience related to pain. “Pain is a physical sensation or signal indicating an event within the body. Suffering is the interpretation of that event and involves thoughts, beliefs, or judgments, and reflects the human experience of pain.”8 O&P practitioners work with patients who report pain when no immediate cause can be identified, or whose pain appears to be disproportionate to their impairments or unrelated to their O&P interventions. Understanding that a patient’s reports may be more related to suffering than pain can help practitioners implement strategies other than device adjustment to address it. By understanding the psychological and sociological factors influencing patients’ experience, practitioners can show empathy, affirm patients, and work with them more effectively to support performance of activities and participation.

Adherence to the Treatment Plan

A 2008 review identified 25 factors related to adherence to treatment plans (compliance).13 Most of these factors are related to environmental and personal factors of the ICF, not biological issues related to patients’ conditions. It is easy to focus only on each patient’s responsibility to adhere to a treatment plan and overlook environmental barriers that complicate adherence. Practitioners who can work with nonadherent patients in a nonjudgmental manner are better able to support them in finding their own solutions to these barriers. For example, patients who have jobs with limited flexibility and time off have more difficulty keeping appointments and arriving on time. A compassionate understanding and collaboration between practitioners and patients are more likely to improve adherence than criticism of missed appointments.

Closing Thoughts

The medical model makes it easy to disregard environmental or personal factors, or to acknowledge them only to the extent that they indicate patients’ responsibility for their own health and relieve practitioners of responsibility. While the choices individuals make clearly influence their health and function and can exacerbate their disability, practitioners with a more holistic understanding recognize that many of these factors are either outside of patients’ direct control or represent significant barriers that are experienced disproportionately by certain populations.

Faith Lagay, PhD, director of the Ethics Resource Center of the American Medical Association, notes that “it is humbling, in a way, to note medicine’s re-attention to lifestyle and environment in the late 20th and early 21st century….Yet, we are coming to realize more and more that the same germ or gene affects different people differently. As the Hippocratics turned their focus away from the supernatural and toward the individual patient, the contemporary physician, too, knows that neither germs nor genes are sacred; successful treatment begins with understanding the individual patient.”1

John T. Brinkmann, MA, CPO/L, FAAOP(D), is an associate professor at Northwestern University Prosthetics-Orthotics Center. He has over 30 years of experience in patient care and education.