Hugh Herr, the director of an M.I.T. laboratory that pursues the “merging of body and machine,” grew up in a Mennonite family outside Lancaster, Pennsylvania. He and his brothers—he was the youngest of five children—often helped their father, a builder, lay shingles, install drywall, and strip wires. During the summer, the family visited places like Alaska and the Yukon in their camper van, and the kids frequently set out alone to hike and rock climb. “When I was eleven, I was this climbing prodigy, climbing things most adults couldn’t do,” Herr told me. “When I was fifteen and sixteen, I started climbing things that no adults had ever done. And then, when I was seventeen, the accident happened.”

Rock climbers call bouldering moves “problems,” and the most difficult section of a route is the “crux.” The young Herr spent days imagining difficult ascents, plotting a path across slots, cracks, and overhangs as one might work through a complex question in geometry or physics. Then he would go out and become the first person to ascend, say, a rock face on the Shawangunk Ridge. (By tradition, the person who makes the first ascent gets to name the route. The chosen names are often kooky: Moby Grape, They Died Laughing, Lonesome Dove, Millennium Falcon.) Herr sometimes did what’s known as free-solo climbing. “I’ll never forget the day I climbed two thousand feet without a rope,” he told me. “All your sensations are heightened. It’s a remarkable feeling of one’s physical control and power.”

In January, 1982, when Herr was a junior in high school, he and a friend, Jeff Batzer, set off to ice-climb Huntington Ravine, in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. They then planned to hike an additional mile or so to the peak of Mt. Washington, a popular destination that is notorious for fast-changing conditions. (It has been said to have the worst weather in the world.) According to the Mount Washington Avalanche Center, about twenty-five people have to be rescued each year, and more than a hundred people have died on the mountain.

Herr and Batzer, who were experienced and very fit, ascended the ice of Huntington Ravine without much difficulty. They figured that if they had trouble on Mt. Washington they could always turn around. A few hundred feet along the trail, however, they encountered winds of up to ninety miles per hour. Visibility was poor. They had to shout to hear each other. While retreating downhill, they lost their way. Several times, Herr’s feet broke through ice into a freezing stream.

The two spent three nights in an isolated valley, in extreme cold. Herr didn’t think that they would survive for even one night. But he wasn’t accounting for the benefits of being with another person. “You can hug them,” Herr has said. “You dramatically reduce the surface area of the dual body, but you double the heat source.” The boys had all but given up when, on the fourth day, a woman out snowshoeing, following what she thought were moose tracks, came across the two young men. They wondered if they were hallucinating; she gave them raisins and a sweater and hurried to get help. They later learned that a search party had spent days out in the snow looking for them.

To stave off gangrene, Batzer had a thumb, several fingers, a foot, and a portion of one leg amputated. Herr had both legs removed below the knee. He was fitted with leg prostheses that had sockets made of plaster; he was warned that putting too much stress on them could crack them. “I was, like, ‘We’ve gone to the moon, and this is it?’ ” he told me. When a prosthetist brought out a box of feet for Herr to choose from, Herr asked if there were any narrow enough to fit inside climbing shoes. “I wanted to get back on the horse,” he told me. “Climbing was my life.”

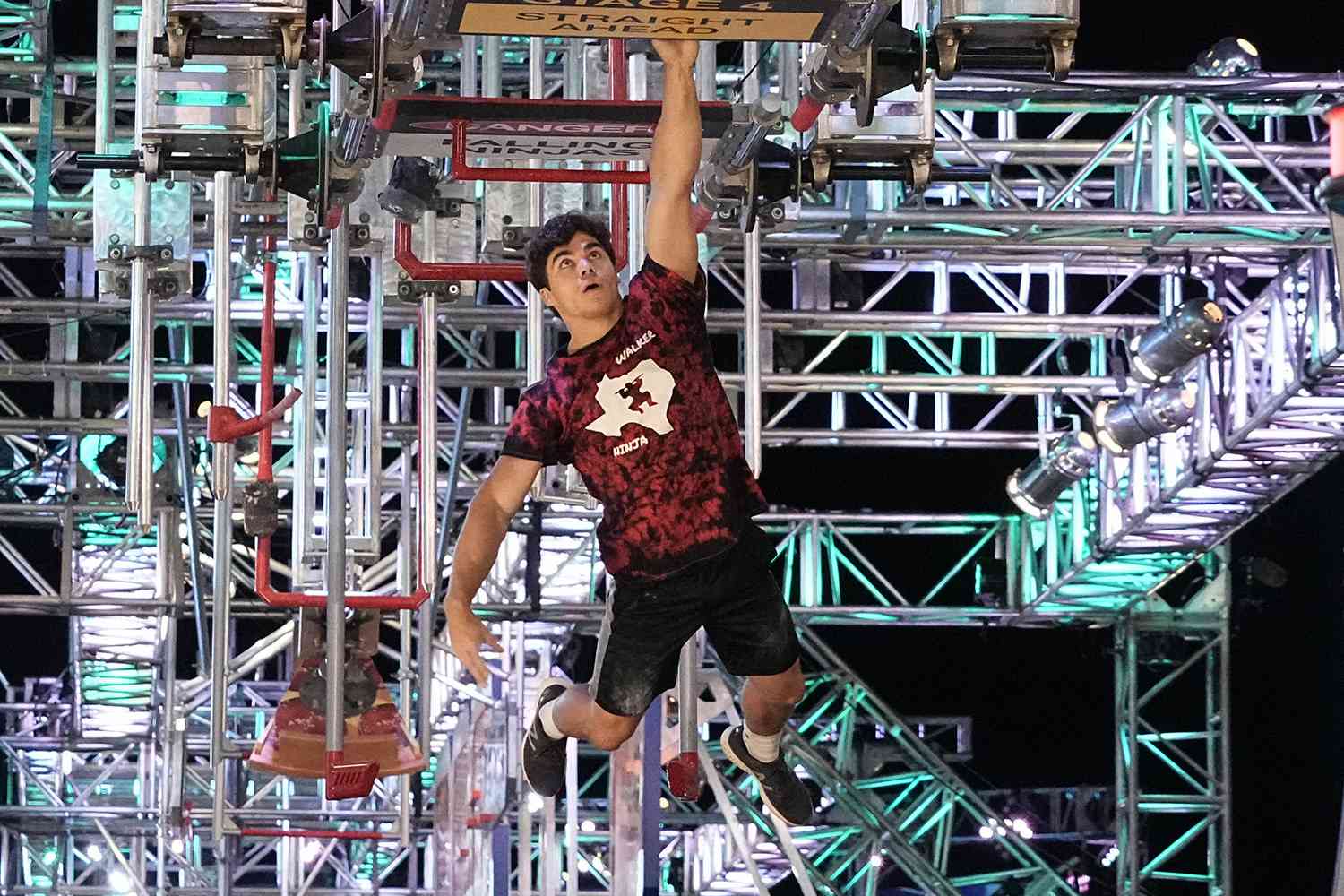

In rehab, Herr got in trouble for, literally, climbing the walls. A few months later, when he was on crutches, he and his brother Tony made their way to the base of a familiar mossy rock face in Pennsylvania, and Herr scaled it. He felt free and strong. And without his lower legs he was, he said, “like, fourteen pounds lighter.” Climbing was easier for him than walking with his prostheses; it was also much less painful. “My dad was, like, If you want to climb, climb. Invent stuff.”

Herr had studied metal fabrication at a nearby vocational school—he had chosen his high-school classes in a way that would leave his schedule open for climbing. He started building prostheses with custom features, such as feet that could grip ice and pointed toes that could be wedged into cracks. “One year after the accident, I was climbing as well as I did before,” he said. Jim Ewing, a climbing friend who was Herr’s roommate around that time, told me, “I watched him become one of the strongest rock climbers in the world—and that was with bilateral amputations.” Herr made a first ascent of a route up Sky Top Ridge, in the Shawangunks, and he christened it Footloose and Fancy Free. (One of his prosthetic feet broke off when he fell and was caught by a rope.) He took on increasingly difficult climbs: City Park, in Washington State, and Liquid Sky and Stage Fright, in New Hampshire. In May, 1983, he appeared on the cover of Outside magazine. In the photo, he’s wearing a bandanna tied around his head; his prosthetic legs are painted with red-and-blue stripes reminiscent of athletic socks. Two pairs of feet, neither attached, are nearby.

But, by 1985, Herr was worrying about the strain on his body. He thought about going to college, which would give him the education he needed to build even more advanced prostheses. “I was imagining limbs where I could run faster than a person with biological limbs,” he told me. “I was imagining non-anthropomorphic structures like legs with wings, and I could fly. I had no idea, obviously, how to do that.” He enrolled at Millersville University, a public school near Lancaster. Herr said that as a teen-ager he’d had such a limited grasp of math that he couldn’t have calculated ten per cent of a hundred. After two years of relentless studying, however, he had advanced to quantum mechanics. “What had been a climbing obsession became an academic obsession,” he said. He thought that maybe his aptitude for mathematics had come in part from all the problem-solving he did as a climber.

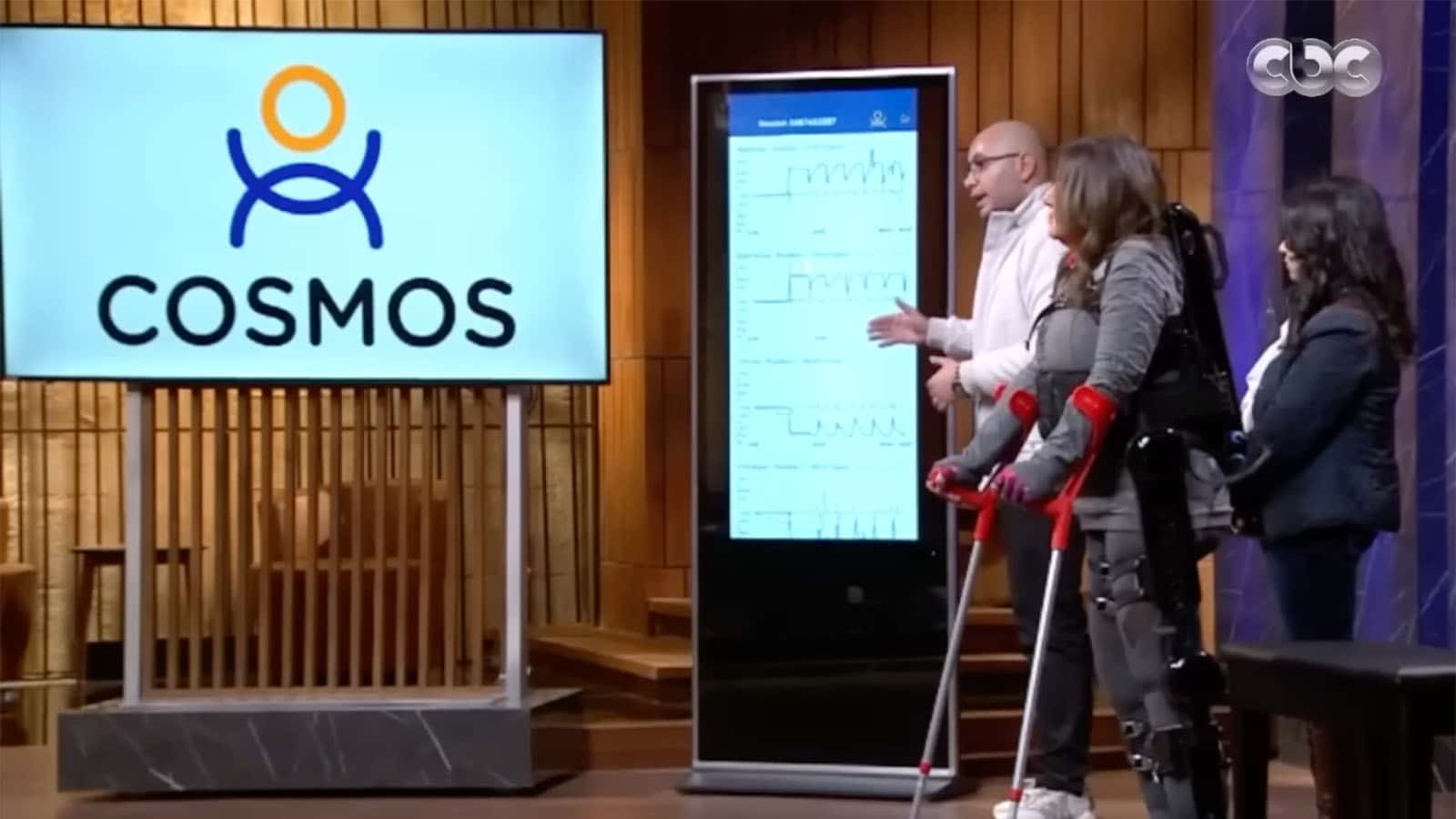

One summer, Herr started developing an adjustable socket for his prostheses, which tended to loosen as swelling in his legs ebbed in the course of a day. He and a prosthetist friend, Barry Gosthnian, who had been a mechanic in the Air Force, had talked about using inflatable bladders, and Herr tried to make some from various materials. Finally, after the seventeenth prototype, he had something that worked. Herr ultimately got a master’s degree in mechanical engineering, from M.I.T., and a Ph.D. in biophysics, from Harvard. He started the M.I.T. Media Lab’s Biomechatronics Group, which uses neurology and engineering to “restore function to individuals who have impaired mobility.” (He is also a director of the K. Lisa Yang Center for Bionics.) At M.I.T., he led the development of a robotic foot-and-ankle prosthesis called the BiOM, which has three microprocessors and six sensors and is tuned to a user’s gait. He started using one himself; in 2011, Time named him the “Leader of the Bionic Age.” Swapping out the powered ankle for a passive spring device, Herr said, felt like stepping off a moving walkway at the airport.

Still, the sophistication of prostheses was limited by the way leg amputations were performed. Surgeons traditionally sew down residual muscles when they amputate a limb. There are good reasons for this—padding the bone is one—but it also severely restricts how much the muscles can move, leading to atrophy. Herr feels as if his legs are still there, but locked into rigid ski boots. The movements of his prostheses and his phantom limbs are out of synch.